The term ‘Holdout’ is the name given to a mechanical contrivance, constructed with the object of enabling the card-sharper to ‘hold-out,’ or conceal one or more cards, until such time as he finds that they will be useful to him by turning the balance of fortune in his favour at some critical point of the game. They are obviously unavailable in those games where the whole pack is distributed among the players, as the cards abstracted must in that case necessarily be missed.

It will be seen, then, that although the name may appear clumsy and puerile, it is notwithstanding well chosen and expressive. The gambler ‘holds out’ inducements to the cheat; the market, provided by cheating, ‘holds out’ inducements to the manufacturer; the manufacturer ‘holds out’ inducements to purchase his machines; and the machines themselves ‘hold out’ inducements which very few sharpers can resist. It is like the nursery-rhyme of the dog that was eventually ‘purwailed on’ to get over the stile.

As far as we have yet traveled upon our explorations into the regions of fraud and chicanery, yclept ‘sharping,’ our path has been, comparatively speaking, a rosy one. The way has been by no means intricate, and the difficulties we have had to encounter have been but few. At this point, however, the course runs through a region which is, to some extent, beset with thorn and bramble, in the guise of mechanical contrivances having a more or less complex character. The non-technical reader, however, has no cause for being appalled at the nature of the ground which he is invited to traverse; the author undertakes to render his traveling easy, and to put him through, as it were, by ‘Pullman-Express.’ One should always endeavour to popularise science whenever the opportunity serves. The mechanically minded reader, at any rate, will revel in the examples of human ingenuity—and corruptibility—which are here presented for the first time to his admiring gaze.

As in all other instances of means well-adapted to a given end, these utensils of the holdout persuasion have taken their origin from extremely simple and antiquated devices. Perhaps we are not correct in saying ‘extremely antiquated,’ since ‘Cavendish’ is of opinion that cards have not been invented more than five hundred years. Those, however, who attribute their invention to the Chinese, æons before the dawn of western civilisation, will be inclined to the belief that the ‘Heathen Chinee’ of succeeding ages must have coerced the smiles of fortune, with the friendly aid of a holdout, centuries before the discovery of the land of that instrument’s second or third nativity.

As to this debatable point, however, there is very little hope that we shall ever be better informed than at present. It belongs to the dead things of the dead past; it is shrouded in the mist of antiquity and buried beneath the withered leaves of countless generations; among which might be found the decayed refuse of many a family tree, whose fall could be directly traced to the invention of the deadly implements known as playing cards. Do not let the reader imagine for a moment that I am inveighing against the use of cards, when employed as an innocent means of recreation. That is not my intention by any means. Such a thing would savour of narrow-mindedness and bigotry, and should be discouraged in every possible way. The means of rendering our existence here below as mutually agreeable as circumstances will permit are by no means so plentiful that we can afford to dispense with so enjoyable a pastime as a game of cards. It is not the fault of the pieces of pasteboard, that some people have been ruined by their means; it is the fault of the players themselves. Had cards never been invented, the result would have been very similar. Those who are addicted to gambling, in the absence of cards, would have spun coins, drawn straws, or engaged in some other equally intellectual recreation. When a man has arrived at the state of mind which induces him to make ‘ducks and drakes’ of his property, and a fool of himself, there is no power on earth that can prevent him from so doing.

But to return. The earliest account we have of anything in the holdout line is the cuff-box described by Houdin. I for one, however, am inclined to think that there is a slight tinge of the apocryphal in the record as given by him. My reason for this opinion is twofold. In the first place the description is singularly lacking in detail, considering Houdin’s mechanical genius; and secondly, the difficulty of constructing and using such an apparatus would be for all practical purposes insuperable. I should say that Houdin had never seen the machine; and that he trusted too implicitly to hearsay, without exercising his judgment. Of course there is nothing but internal evidence to support this view; still, I cannot help believing that part at least of the great Frenchman’s account must be taken ‘cum grano.’ In any event, however, we are bound to admit that something in the nature of a holdout was known to some persons in the early part of the present century.

Houdin entitles the device above referred to—’La boite à la manche;’ and his description is to the following effect.

A box sufficiently large to contain a pack of cards was concealed somewhere in the fore part of the sharp’s coat-sleeve. In picking up the pack, preparatory to dealing, the forearm was lightly pressed upon the table. The box was so constructed that this pressure had the effect of throwing out the prepared or pre-arranged pack previously put into it, and at the same time a pair of pincers seized the pack in use, and withdrew it to the interior of the box, in exchange for the one just ejected. In his autobiography, Houdin recounts an incident in which this box played a prominent part. A sharp had utilized it with great success for some time, but at last the day came when his unlucky star was in the ascendant. The pincers failed to perform their function properly, and instead of removing the genuine pack entirely, they left one card upon the table. From the description given of the apparatus, one may imagine that such a contingency would be very likely to arise. The dupe of course discovered the extra card, accused the sharp of cheating—and not without reason, it must be admitted—challenged him to a duel, and shot him. Serve him right, you say? Well, we will not contest the point.

The substitution of one pack for another appears to be the earliest conception of anything approximate to the process of holding-out cards until they are required. All sorts of pockets, in every conceivable position, appear to have been utilised by the sharps of long ago, for the purpose of concealing the packs which they sought to introduce into the game. This necessarily could only be done at a period when plain-backed cards were generally used. The sharp of to-day would want a goodly number of pockets, if it were necessary for him to be able to replace any pattern among the cards which he might be called upon to use.

Holding out, however, in the true sense of the term, became a power in the hands of the sharp only with the introduction, and the reception into popular favour, of games such as Poker, in which the cards are not all dealt out, and the possession of even one good card, in addition to a hand which, apart from fraud, proves to be decent, is fraught with such tremendous advantages to the sharp who has contrived to secrete it.

The earliest example of a card being systematically held out until it could be introduced into the game with advantage to the player, is probably that of the sharp who, during play, was always more or less afflicted with weariness, and consequently with a perpetual desire to stretch himself and yawn. It was noticed after a while that he always had a good hand after yawning; a singular fact, and unaccountable. Doubtless the occultists of that day sought to establish some plausible connection between the act of stretching and the caprices of chance. If so, there is very little question that, according to their usual custom, they discovered some super-normal, and (to themselves) satisfactory hypothesis, to account for the influence of lassitude upon the fortunes of the individual. In accordance with the usual course of events in such instances, however, the occult theory would be unable to retain its hold for long. The super-normal always resolves itself into the normal, when brought under the influence of practical common-sense. In this particular case the explanation was of the simplest. Having secreted a card in the palm of his hand, the sharp, under cover of the act of stretching, would just stick it under the collar of his coat as he sat with his back to the wall. When the card was required for use, a second yawn with the accompanying stretch would bring it again into his hand. This, then, was the first real holdout—the back of a man’s coat collar.4

Since that time the ingenuity of the cheating community has been unremittingly applied to the solution of the problem of making a machine which would enable them to hold out cards without risk of detection. That their efforts have been crowned with complete success we have the best of reasons for believing, inasmuch as holdouts which can be used without a single visible movement being made, and without the least fear of creating suspicion, are articles of commerce at the present moment. You have only to write to one of the dealers, inclosing so many dollars, and you can be set up for life. No doubt you can obtain the names and addresses of these gentlemen without difficulty; but since the object of this book is not to supply them with gratuitous advertisement, their local habitation will not be given herein, although their wares are prominently mentioned.

In order that the reader may fully appreciate the beauty and value of the latest and most improved devices, we will run lightly over the gamut of the various instruments which have been introduced from time to time. This course is the best to pursue, since even among the earlier appliances there are some which, if well-worked, are still to be relied upon in certain companies, and indeed are relied upon by many a sharp who considers himself ‘no slouch.’

There is every reason to believe that the first contrivance which proved to be of any practical use was one designated by the high-sounding and euphonious title of ‘The Bug.’ Your sharp has always an innate sense of the fitness of things, and an unerring instinct which prompts him to reject all things but those which are beautiful and true. Ample evidence of this is not wanting, even in such simple matters as the names he gives to the tools employed in his handicraft.

‘The Bug’ would appear to be an insect which may be relied upon at all times, and in whose aid the fullest confidence may be placed. In fact, there is a saying to the effect that the bug has never been known to fail the enterprising naturalist who has been fortunate enough to secure a specimen, and that it has never been detected in use.

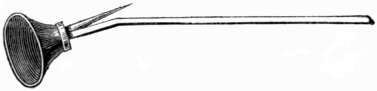

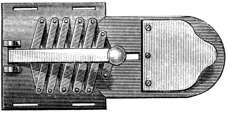

This entomological curiosity is illustrated in fig. 24, and is thus described in the catalogue of one indefatigable collector.

‘The Bug.’ A little instrument easily carried in your vest pocket, that can be used at a moment’s notice to hold out one or more cards in any game. Simple yet safe and sure. Price $1,00.

Such then are the general characteristics of the species; but since the reader will probably desire a more intimate acquaintance with its habits and its structural details, the following description is appended.

In its essential features the bug is simply a straight piece of watchspring, bent—as Paddy might say—at one end. The end nearest the bend is inserted into the handle of a very small shoemaker’s awl. There is nothing else ‘to it’ whatever. The point of the awl is stuck into the under side of the table, in such a manner that the spring lies flat against the table top, or nearly so, the point of the spring projecting beyond the edge of the table to the extent of about one-eighth of an inch.

The cards having been dealt out (say for Poker), the sharp takes up those which have fallen to his hand, and stands them on edge upon the table, with their faces towards him, holding them with both hands. The card or cards which he wishes to hold out are then brought in front of the others, and with the thumbs they are quietly slid under the table between it and the spring. In this position they are perfectly concealed, and may be allowed to remain until required. When again wanted, these cards are simply pulled out by the two thumbs, as the sharp draws his other cards towards him with a sweeping motion. Thus, by selecting a good card here and there, as the succeeding hands are played, the sharp acquires a reserve of potential energy sufficient to overcome a great deal of the inertia with which he would otherwise be handicapped by the fluctuations of fortune.

The next form of holdout which falls beneath our notice is that known as the ‘Cuff Holdout.’ Let us see how the genius of the maker describes it.

‘Cuff Holdout. Weighs two ounces, and is a neat invention to top the deck, to help a partner, or hold out a card playing Stud Poker, also good to play the half stock in Seven Up. This holdout works in shirt sleeves and holds the cards in the same place as a cuff-pocket. There is no part of the holdout in sight at any time. A man that has worked a pocket will appreciate this invention. Price, by registered mail, $10,00.’

The cuff-pocket, above alluded to, was a very early invention. As its name indicates, it was a pocket inside the coat sleeve, the opening to which was situated on the under side at the seam joining sleeve and cuff. In fig. 25 ‘a’ denotes the opening of the pocket.

In a game of Poker it would be employed as follows. Whilst shuffling the cards, the sharp would contrive to get three of a kind at the top of the pack. He would then insert his little finger between these three cards and the rest, the pack being in the left hand. Then holding his hand in front of him he would reach across it with the other, for the (apparently) simple purpose of laying down his cigar, upon his extreme left, or if he were not smoking he might lean over in the same manner to ‘monkey with his chips’ (i.e. to arrange his counters). In this position the orifice of the pocket would come level with the front end of the pack, the latter being completely covered by his right arm. This would give him an opportunity of pushing the three selected cards into the pocket, where they would remain until he had dealt out all the cards and given off all the ‘draft’ except his own. Still holding the pack in his left hand, and his hand in front of him, he would again cross his right hand over, this time for the purpose of taking up and examining his own hand of cards, which he had taken the precaution of dealing well to the left, to give him an excuse for crossing his hands. He would then remove the cards from the cuff-pocket to the top of the pack, and lay the whole down upon the table. His maneuvering having been successful so far, he would now throw away three indifferent cards from his hand and deliberately help himself to the three top cards of the pack. These, of course, would be the three (aces for preference) which he had previously had concealed in the pocket. Thus, he is bound to have a ‘full,’ in any case. If he had been so fortunate as to possess another ace among the cards which fell to his hand on the deal, he would have a ‘four’; which can only be beaten when ‘straights’ are played by a ‘straight flush’—in other words, a sequence of five cards, all of the same suit. His chances of ‘winning the pot,’ then, are infinite as compared with those of the other players.

The great disadvantage of the cuff-pocket was the difficulty of removing the cards when once they had been put into it. To facilitate their removal, therefore, the pocket was sometimes provided with a slide, having a projecting stud, which could be drawn with the finger. This would throw the cards out into the hand.

This description will serve to enlighten the reader as to the advantages to be gained by substituting the cuff-holdout in place of the pocket which it is intended to supplant. It fulfils its purpose in a much more perfect manner, being far easier to use, and requiring less skill on the part of the operator.

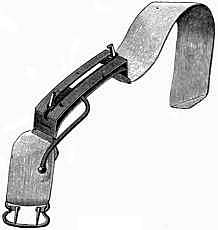

Referring to fig. 26, it will be seen that this instrument consists practically of a pair of jaws, which, being movable, will separate sufficiently to allow a card to be held between them. These jaws are drawn towards each other by means of an elastic band slipped over them. Elastic is the material commonly used in the springs of holdouts, being readily replaced when worn out or otherwise deteriorated. The projecting lever situated at the side of the machine is for the purpose of separating the jaws when the cards are to be withdrawn. The act of pressing it to one side releases the cards, and at the same time throws up a little arm from the body of the holdout, which thrusts them out.

The machine is strapped around the fore-arm with the jaws underneath, and is worn inside the sleeve of the coat or, if playing in shirt-sleeves, inside the shirt-sleeve. Acting from the inside it will hold a card or cards against the under surface of the sleeve, in which position they are concealed from view by the arm. The hands being crossed, as in the case of the cuff-pocket, the cards are simply slipped between the jaws, where they are held until required. The hands being crossed for the second time, the lever is pressed and the cards fall upon the top of the pack, which is held underneath at the moment. This operation is termed technically ‘topping the deck.’ Fig. 27 shows the manner in which the cards are held by this machine.

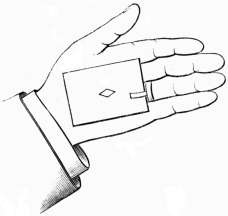

An extremely simple form of appliance, and one which may be utilised with effect, is that known as the ‘ring holdout.’ It is merely a small piece of watch-spring fitted with a clip, enabling it to be attached to an ordinary finger-ring. Between this spring and palm of the hand the cards are held (fig. 28).

With a little practice the deck may be topped, hands made up or shifted, and cards held out in a manner which is far safer and better than any ‘palming,’ however skillfully it may be done. Needless to say, the cards used must not be too large, or the operator’s hand too small, if this device is to be employed.

We now come to the subject of coat and vest machines, among which are to be found some of the finest examples of mechanical genius as applied to the art of cheating.

The earliest vest machine was a clumsy utensil covering nearly the whole of the wearer’s chest. It was called—not inaptly—by the gambling fraternity of the time the ‘Breast-plate.’

Like all other ideas, however, which contain the germ of a great principle, this conception has been improved upon, until it has developed into an invention worthy of the noble end which it is intended to fulfil.

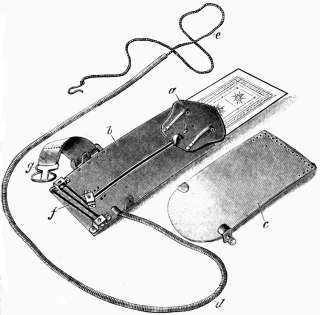

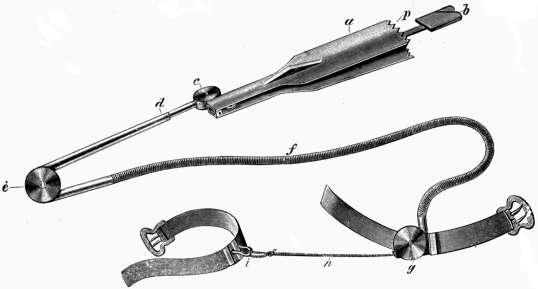

In its latest and most improved form, as widely used at the present day, it is illustrated in fig. 29.

As a thorough acquaintance with the construction and working of this machine will be of great assistance to us in arriving at an understanding of those which follow, we will go into it somewhat exhaustively with the aid of the lettering in the illustration.

Referring then to fig 29, a is a slide which is free to move in the direction of the length of the base-plate b. It is held in position and guided by means of fittings which pass through the slot cut in the base-plate. This slide is composed of two thin plates of metal between which the cards are held as shown, and is protected by the cover c, which is removable, and which is hinged when in use to lugs provided for the purpose upon the base-plate. The ends of base-plate and cover farthest from the hinge-joint are each pierced with a row of small holes. These are to facilitate the sewing of the apparatus to the divided edges of a seam.

Attached to the upper surface of the slide will be seen thin strips of metal, bent into somewhat of the form of a bow. In practice these are covered with cloth, to prevent the noise they would otherwise make in rubbing against the cover. As the slide moves forward into the position it occupies in the figure these projecting strips, pressing against the cover, tend to thrust base-plate and cover apart. This action separates the edges of the seam to which those parts of the apparatus are respectively sewn, and provides an aperture for the entrance or the exit of the slide, together with the cards it is holding out. As the slide returns to the other end of the base-plate, the cloth-covered strips fall within the curvature of the cover, thus allowing the edges of the seam to come together; and when the slide is right home, the central projecting strip passes beyond the hinge-joint, thus tending to press the free ends of base-plate and cover into intimate contact. The opening which has been fabricated in the seam is thus securely closed, and nothing amiss can be seen.

The to-and-fro movement of the slide is effected in the following manner. Attached at one end to the base-plate is a flexible tube d, consisting simply of a helix of wire closely coiled. Through this tube passes a cord e, one end of which is led around pulleys below the base-plate, and attached to the slide in such a manner that, when the cord is pulled, the slide is drawn into the position shown. To the other end of the cord is fastened a hook for the purpose of attaching it to the ‘tab’ or loop at the back of the operator’s boot. It may be here mentioned that the cord used in this and all similar machines is a very good quality of fishing-line. The slide is constantly drawn towards its normal position within the machine by the piece of elastic f. The band g with the buckle attached is intended to support the machine within the coat or vest.

The foregoing description necessarily partakes of the nature of Patent Office literature, but it is hoped that the reader will be enabled to digest it, and thereby form some idea of this interesting invention.

Although it is both a coat and vest machine, this apparatus is more convenient to use when fastened inside the coat, as the front edges of that garment are readier to hand than those of the waistcoat. The edge of the right breast is unpicked, and the machine is sewn into the gap. The flexible tube is passed down the left trouser-leg, inside which the hook hangs at the end of the cord ready for attachment to the boot.

When the operator is seated at the table, he seizes a favourable opportunity of hooking the cord to the loop of his boot, and all is ready. Having obtained possession of the cards he wishes to hold out, he holds them flat in his hand, against his breast. Then, by merely stretching his leg, the cord is pulled, the seam of the coat opens (the aperture being covered, however, by his arm) and out comes the end of the slide. The cards are quietly inserted into the slide; the leg is drawn up, and—hey, presto! the cards have disappeared. When they are again required, another movement of the leg will bring them into the operator’s hand.

One can readily see how useful a device of this kind would be in a game of the ‘Nap’ order. Having abstracted a good hand from the pack (five cards ‘never would be missed’) it could be retained in the holdout as long as might be necessary. Upon finding oneself possessed of a bad hand, the concealed cards could be brought out, and the others hidden until it came to one’s turn to deal, and then they could be just thrown out on to the pack.

The price of this little piece of apparatus is $25.00, and, doubtless, it is worth the odd five, being well made and finished up to look pretty. In fact, it is quite a mantelboard ornament, as most of these things are. Evidently, the sharp, whilst possessing the crafty and thieving instincts of the magpie, has also the magpie’s predilection for things which are bright and attractive. Therefore his implements are made resplendent with nickel and similar precious metals. Although electroplating or something of the kind is necessary to prevent rust and corrosion, one would be inclined to think that articles which are intended to escape observation would be better adapted to their end if they were protected by some method just a trifle less obtrusive in its brilliancy. However, that is not our business. If the buyers are satisfied, what cause have we to complain?

The ‘Kepplinger’ vest or coat machine, which is referred to in the Catalogue (p. 293), is exactly the same thing as that just described, with the addition of Kepplinger’s method of pulling the string, which will be described further on.

The ‘Arm Pressure’ vest machine, mentioned in the same Catalogue, is a modification of the old ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ sleeve holdout, to which we shall have occasion to revert presently. In an earlier edition of the Catalogue the arm-pressure machine is thus eulogised:—

‘New Vest Machine. Guaranteed to be the best Vest Machine made. This machine weighs about three ounces, and is used half-way down the vest, where it comes natural to hold your hands and cards. The work is done with one hand and the lower part of the same arm. You press against a small lever with the arm (an easy pressure of three-quarters of an inch throws out the cards back of a few others held in your left hand), and you can reach over to your checks or do anything else with your right hand while working the Hold-Out. The motions are all natural and do not cause suspicion. The machine is held in place by a web belt; you don’t have to sew anything fast, but when you get ready to play you can put on the machine and when through can remove it in half a minute. There are no plates, and no strings to pull on, and no springs that are liable to break or get out of order. This machine is worth fifty of the old style Vest Plates for practical use, and you will say the same after seeing one.’

The statement guaranteeing this to be the best vest machine ever made has been expunged of late, as will be noticed in the reproduction of the Catalogue upon page 294. In reality it is not nearly so efficient as the Kepplinger, all statements and opinions to the contrary notwithstanding. Its construction will be readily understood from the description of the ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ which follows next in order.

This brings us, then, to the subject of sleeve machines, or appliances whereby the sharp, like Ah Sin, the ‘Heathen Chinee,’ who understood so well ‘the game he did not understand,’ is enabled to have a few cards up his sleeve. ‘Up his sleeve!’ How those words suggest the explanation so often given by the innocent-minded public to account for the disappearance of the various articles which slip so nimbly through a conjurer’s fingers. And yet, if they only knew it, that is about the last place in the world that a conjurer, as a rule, would use as a receptacle for anything. Of course there is no Act of Parliament to prevent him, should he desire to do so; but that’s another story. With the sharp, however, there are several Acts of Parliament to prevent him from using his sleeve for any such purpose; and yet he often resorts to it. How true is the saying that ‘one man may steal a horse, whilst another may not look over the hedge.’

As far as can be ascertained, the ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ was the forerunner of all other sleeve holdouts. It was fastened to the under side of the fore-arm, and worked by pressure upon the table. Its construction was essentially that of a pair of lazy-tongs, arranged as in figs. 30 and 31. The base-plate carrying the working parts was curved so as to lie closely against the arm and hold the machine steady whilst in use. The ‘lazy-tongs’ device was fixed to the base-plate at one end, the other being free to move, and carrying the clip for the cards. Situated at an angle above the ‘tongs’ was a lever, also attached at one end to the base-plate, the other end terminating in a knob. Half-way down this lever was hinged a connecting-rod, joining the lever with the second joint of the ‘tongs.’ Pressure being applied to the knob, the connecting-rod would force out the joint to which it was attached; and the motion being multiplied by each successive joint, the clip was caused to protrude beyond the coat cuff. In this position the card could be inserted or removed as in the cases already noticed. The clip was returned to its place within the sleeve by means of a rubber band.

Some of these ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ sleeve machines are made to work by pulling a string, after the manner of the coat and vest machine already described. Those advertised at $50.00 are of this description.

The advantage of a machine of this kind is of course found in the fact that the cards are brought directly into the hand. This particular form, however, was very difficult to use, as the cards were always liable to catch in the cuff, a circumstance which is obviously much to the detriment of the apparatus. There is also the further disadvantage of being compelled to wear an abnormally large shirt-cuff, which in itself would attract attention among men who had their wits about them.

The enormous facilities for un-ostentatious operation afforded by a machine working inside the sleeve were too readily apparent to allow of the sleeve holdout falling into disuse. It was the kind of thing which must inevitably be improved upon, until it became of practical utility. And such has been the case. The very finest holdout the world has ever seen is that known as the Kepplinger or San Francisco. This machine in its latest forms is certainly a masterpiece. Yet so little appreciation has the world for true genius, that the inventor of this marvellous piece of apparatus is practically unknown to the vast majority of his fellow-men.

Kepplinger was a professional gambler; that is what he was. In other words, he was a sharp—and of the sharpest.

As to the date at which this bright particular Star of the West first dawned upon the horizon of ‘Tom Tiddler’s Ground’ deponent sayeth not. Neither have we any substantial record of the facts connected with the conception and elaboration of that great idea with which his name is associated. Of its introduction into the field of practical utility, however, and its subsequent revelation to the fraternity to whom its existence was of the utmost consequence, the details are available, and therefore may be revealed. The event occurred in this wise, as follows, that is to say:—

In the year of grace 1888, Kepplinger, the inventor, gambler and cheat, was resident and pursuing his daily avocations in the city known colloquially as ‘Frisco.’

Now it is a singular feature of human nature that, whatever a man’s calling may be, however arduous or exacting, he becomes in course of time so much a creature of habit that he is never really happy apart from it. One may suppose that it is the consciousness of ability to do certain things, and to do them well, which accounts for this fact. At any rate, the fact remains. We are all alike in this respect—especially some of us. The barrister at leisure will prefer to sit in Court and watch another conducting a case; the actor with an evening to spare will go and see someone else act; the omnibus-driver with a day off will perch himself upon a friend’s vehicle, and ride to and fro; and the sharp will infallibly spend his leisure moments in gambling. When there are no dupes to be plundered, no ‘pigeons’ who have a feather left to fly with, the ‘rooks’ will congregate in some sequestered spot, and enjoy a quiet game all to themselves. And they play fairly? Yes—if they are obliged to do so; not otherwise. They will cheat each other if they can. Honour amongst thieves! Nonsense.

In 1888, then, Kepplinger’s relaxation for some months consisted of a ‘hard game’ with players who were all professional sharps like himself. The circle was composed entirely of men who thought they ‘knew the ropes’ as well as he did. In that, however, they were considerably in error. He was acquainted with a trick worth any two which they could have mentioned. However much the fortunes of the others might vary, Kepplinger never sustained a loss. On the contrary, he always won. The hands he held were enough to turn any gambler green with envy, and yet, no one could detect him in cheating. His companions were, of course, all perfectly familiar with the appliances of their craft. Holdouts in a game of that description would have been, one would think, useless encumbrances. The players were all too well acquainted with the signs and tokens accompanying such devices, and Kepplinger gave no sign of the employment of anything of the kind. He sat like a statue at the table, he kept his cards right away from him, he did not move a muscle as far as could be seen; his opponents could look up his sleeve almost to the elbow, and yet he won.

This being the condition of affairs, it was one which could not by any stretch of courtesy be considered satisfactory to anyone but Kepplinger himself. Having borne with the untoward circumstances as long as their curiosity and cupidity would allow them, his associates at length resolved upon concerted action. Arranging their plan of attack, they arrived once again at the rendezvous, and commenced the game as usual. Then, suddenly and without a moment’s warning, Kepplinger was seized, gagged, and held hard and fast.

Then the investigation commenced. The great master-cheat was searched, and upon him was discovered the most ingenious holdout ever devised.

What did the conspirators do then? Did they ‘lay into him’ with cudgels, or ‘get the drop’ on him with ‘six-shooters’? Did they, for instance, hand him over to the Police? No! ten thousand times no! They did none of those things, nor had they ever any intention of doing anything of the kind. Being only human—and sharps—they did what they considered would serve their own interests best. A compact was entered into, whereby Kepplinger agreed to make a similar instrument to the one he was wearing for each of his captors, and once again the temporary and short-lived discord gave place to harmony and content.

Had Kepplinger been content to use less frequently the enormous advantage he possessed, and to have exercised more discretion in winning, appearing to lose sometimes, his device might have been still undiscovered.

It was thus, then, that the secret leaked out, and probably without the occurrence of this ‘little rift within the lute’—or should it be loot?—the reader might not have had this opportunity of inspecting the details of the ‘Kepplinger’ or ‘San Francisco’ holdout.

This form of sleeve machine will be easily understood by the reader who has followed the description of the coat and vest holdout already given upon referring to fig. 32 upon the opposite page, the illustration being a diagrammatic representation of the various parts of the apparatus.

It is evident that we are here brought into contact with a greater complexity of strings, wheels, joints, tubes, pulleys, and working parts generally than it has hitherto been our lot to encounter. There is, however, nothing which is superfluous among all these things. Every detail of the apparatus is absolutely necessary to secure its efficiency. The holdout itself, a, is similar in construction to the coat and vest machine, except that it is longer, and that the slide b has a greater range of movement.

The machine is worn with a special shirt, having a double sleeve and a false cuff. This latter is to obviate the necessity of having ‘a clean boiled shirt,’ and the consequent trouble of fixing the machine to it, more frequently than is absolutely necessary.

It will be seen that the free ends of the base-plate and cover, instead of being pierced with holes, as in the vest machine, are serrated, forming a termination of sharp points (p). These are for the purpose of facilitating the adaptation of the machine to the operator’s shirt-sleeve, which is accomplished in the following manner. In the wristband of the inner sleeve a series of little slits is cut with a penknife, and through these slits the points upon the base-plate are thrust. The base-plate itself is then sewn to the sleeve with a few stitches, one or two holes being made in the plate to allow this to be done readily. Thus the points are prevented from being accidentally withdrawn from the slits, and the whole apparatus is firmly secured to the sleeve. In the lower edge of the false cuff slits are cut in a similar manner, and into these the points of the cover are pushed. The cuff is held securely to the cover by means of little strings, which are tied to holes provided for the purpose in the sides of the cover. These arrangements having been made, the shirt, with the machine attached, is ready to be worn. The operator having put it on, takes a shirt stud with rather a long stem, and links the inner sleeve round his wrist. Then he fastens the false cuff to the inner sleeve by buttoning the two lower stud-holes over the stud already at his wrist. Thus, the inner sleeve and the cuff are held in close contact by the base-plate and cover of the machine. Finally, he fastens the outer sleeve over the whole, by buttoning it over the long stud which already holds the inner sleeve and the cuff. Thus, the machine is concealed between the two sleeves. If one were able to look inside the operator’s cuff whilst the machine is in action, it would appear as though the wristband and cuff came apart, and the cards were protruded through the opening. The points, then, are the means whereby the double sleeve is held open while the machine is in operation, and closed when it is at rest. From the holdout, the cord which works the slide is led to the elbow-joint, where it passes around a pulley (c). This joint, like all the others through which the cord has to pass, is what is known as ‘universal’; that is to say, it allows of movement in any direction. From the elbow to the shoulder the cord passes through an adjustable tube (d). The telescopic arrangement of the tube is to adapt it to the various lengths of arm in different operators. At the shoulder-joint (e) is another universal pulley-wheel, which is fastened up to the shoulder by a band of webbing or any other convenient means. At this point begins the flexible tube of coiled wire, which enables the cord to adapt itself to every movement of the wearer, and yet to work without much friction (f). The flexible tube terminates at the knee in a third pulley (g), attached to the leg by a garter of webbing. The cord (h) now passes through an opening in the seam of the trouser-leg and across to the opposite knee, where through a similar opening projects a hook (i), over which the loop at the end of the cord is placed.

It must not be imagined that the sharp walks about with his knees tethered together with a piece of string, and a hook sticking out from one leg; or even that he would be at ease with the knowledge of having a seam on each side unpicked for a distance of two inches or so. That would be what he might call ‘a bit too thick.’ No; when the sharp sits down to the table, nothing of any such a nature is visible. Nor when he rises from the game should we be able to discover anything wrong with his apparel. He is much too knowing for that. The arrangement he adopts is the following:—

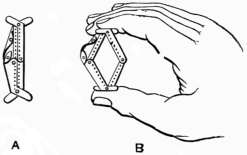

At each knee of the trousers, where the seams are split open, the gap thus produced is rendered secure again, and free from observation, by means of the little spring-clip shown in fig. 33. This contrivance is sewn into the seam, being perforated to facilitate that operation. When closed, it keeps the edges of the opening so well together that one could never suspect the seam of having been tampered with. When it is required to open the gap, the ends of the clip are pressed with the finger and thumb (B, fig 33). This instantly produces a lozenge-shaped opening in the seam, and allows of the connection between the knees being made.

When the sharp sits down to play, then, he first presses open these clips; next, he draws out the cord, which has hitherto lain concealed within the trouser-leg, and brings into position the hook, which, turning upon a pivot, has until now rested flat against his leg: lastly, he passes the loop at the end of the cord over the hook, and all is in readiness. These operations require far less time to accomplish than to describe.

The sharp being thus harnessed for the fray, it becomes apparent that by slightly spreading the knees, the string is tightened, and by this means the slide within the body of the holdout is thrust out, through the cuff, into his hand. The cards which he desires to hold out being slightly bent, so as to adapt themselves to the curve of the cuff, and placed in the slide, the knees are brought together, and the cards are drawn up into the machine.

At the conclusion of the game the cord is unhooked, and tucked back through the seam; the hook is turned round, so that it lies flat; and finally the apertures are closed by pressing the sides of the clips together.

There is one point in connection with the practical working of the machine which it may be as well to mention. The pulley g at the end of the flexible tube is not fixed to the knee permanently, or the sharp would be unable to stand up straight, with the tube only of the requisite length; and if it were made long enough to reach from knee to shoulder whilst he was in a standing position, there would be a good deal too much slack when he came to sit down. This pulley, therefore, is detachable from the band of webbing, and is fixed to it when required by means of a socket into which it fits with a spring-catch.

Such then, is the Kepplinger holdout; and the selling-price of the apparatus complete is $100.00. If there were any inventor’s rights in connection with this class of machinery, doubtless the amount charged would be very much higher. Governments as a rule, however, do not recognize any rights whatever as appertaining to devices for use in the unjust appropriation of other people’s goods or money—at least, not when such devices are employed by an individual. In the case of devices which form part of the machinery of government, the Official Conscience is, perhaps, less open to the charge of prejudice and narrow-mindedness. What is sauce for the (individual) goose is not sauce for the (collective) gander. However, two wrongs would not make a right, and perhaps all is for the best.

Before leaving the subject of holdouts, there is one other form to which it is necessary to refer, viz. the table holdout. It is thus described by the maker:—

‘Table Holdout.—Very small and light. It can be put under and removed from any table in less than half a minute. Works easily from either knee. It will bring three or more cards up into your hand and take back the discards as you hold your hands and cards in a natural position on top of the table.’

This ‘contraption’ is an extremely simple thing, its recommendation being that it accomplishes mechanically what the ‘bug’ requires manipulation to effect. It is[108] constructed on the same principle as the ordinary vest machine, and is fastened to the under side of the table-top by means of a spike, in a similar manner to the table reflector. The string which works the slide terminates, at the end which is pulled, in a hook having a sharp point. The machine being fixed under the table ready to commence operations, the pointed hook is thrust through the material of the trousers just above one knee. When the slide is required to come forward, the knee is dropped a little; and, upon raising the knee again, the slide is withdrawn by its spring, as in all similar arrangements.

By this time the reader will be in a position to understand the nature of the ‘reflector on machine,’ referred to in the last chapter, without needing to be wearied with further details of this particular kind.

Having thus glanced at all the principal varieties of the modern holdout, with one or two of the more ancient ones, it only remains to add a few general remarks to what has been said.

Each class of machine has its own peculiar advantages and disadvantages. Each sharp has his own peculiarities of taste and his own methods of working. Therefore, there is no one kind of appliance which appeals equally to all individuals. Some will prefer one machine; some another. That, of course, is the rule in the world generally. A great deal also depends upon the manners and customs of the country in which the machine is to be used.

For instance, how many card-players are there in England who hold their cards in the manner represented in fig. 34? Very few, I take it. Yet it is a very good method of preventing others from seeing one’s hand. Further, it is the correct way to hold the cards when using the Kepplinger sleeve-machine. The cards are placed flat in one hand, the fingers of the other are pressed upon them in the centre, whilst the thumb turns up one corner to allow of the indices being read. To adopt this method in England, however, would be to arouse suspicion at once, merely because it is unusual. Therefore the vest machine is the best for the English sharp; although no holdout can compare with the Kepplinger in a game of Poker in America.

Although most of these contrivances are simple in operation, the reader must not run away with the idea that their use entails no skill upon the part of the sharp who uses them. That would be far too blissful a state of affairs ever to be achieved in this weary world, where all is vanity and vexation of spirit. Certainly, they do not demand the dismal hours of solitary confinement with hard labour which have to be spent upon some of the manipulative devices and sleight-of-hand dodges; but still they require a certain amount of deftness, which can only be acquired by practice. The following instructions will represent the advice of an expert, given to a novice who proposed to try his hand with a machine at the game of Poker:—

‘Practice at least three weeks or a month with the machine, to get it down fine [i.e. to gain facility of working, both of machine and operator]. Don’t work the machine too much. [Not too often during the game.] In a big game [that is, where the stakes are high] three or four times in a night are enough. Never play it in a small game [because the amount that could be won would be incommensurate with the risk of detection]. Holding out one card will beat any square game [honest play] in the world. Two cards is very strong; but can easily be played on smart people. Three cards is too much to hold out on smart men, as a ‘full’ is too big to be held often without acting as an eye-opener. Never, under any circumstances, hold out four or five. One card is enough, as you are really playing six cards to everyone else’s five. This card will make a ‘straight’ of a ‘flush’ sometimes; or, very often, will give you ‘two pair’ or ‘three’ of a kind. If you are very expert, you can play the machine on your own deal; but it looks better to do it on someone else’s.’

Having digested these words of comfort and advice—precious jewels extracted from the crown of wisdom and experience—we may proceed on our way invigorated and refreshed by the consciousness of having acquired knowledge such as rarely falls to the lot of man to possess.