Although, in the course of our previous wanderings among what may be aptly described as ‘The Groves of Blarney,’ we have already encountered many examples of the various preparations used by the dwellers therein to add new beauties to their everyday requisites, there still remain some to be investigated. These philosophers, in searching for their form of the universal ‘alkahest,’ which turns everything they touch to gold, have contrived to learn many things, besides those we have already looked into. It behoves us, therefore, to follow in their footsteps as far as may be; and, before finally quitting the subject of playing-cards, to complete our information respecting these beautiful and—to the sharp—useful appliances.

We have seen how much may be accomplished by means of judicious preparation of the cards. That is not a discovery which can be ascribed to the present generation of sinners, or the last, or the one before that. No man can say when preparation was first ‘on the cards.’ Some of the devices contained in this chapter are as old as the hills; others are of a more recent date; but, old or new, this book would be incomplete without some description of them. The very oldest are sometimes used even now, in out-of-the-way corners of the world, and among people who are possessors of that ignorance of sharping which is not bliss, at least if they happen to be gamblers.

One of the oldest methods of preparing cards for the purposes of cheating was by cutting them to various shapes and sizes. That this plan is still adopted the reader already knows. We have now to consider the means whereby the sharp is enabled to alter the form of the cards in any way he pleases, with neatness and accuracy.

The most primitive appliance used for the purpose is what is now known as a ‘stripper-plate.’ It consists of two steel bars, bolted together at each end, the length between the bolts being ample to allow a playing-card to be inserted lengthwise between the bars, and screwed up tightly. Fig. 45 illustrates a device of this kind, with a card in situ, ready for cutting. Across the centre of the top plate a slight groove is filed, to facilitate the insertion of the card in a truly central position. The edges of the two plates or bars are perfectly smooth, and are formed so as to give the required curve to the card when cut. In the illustration, the side of the card when cut would become concave. The cutting is managed by simply running a sharp knife or razor along the side of the arrangement. This takes off a thin shred of the card, and, guided by the steel plates, the cut is clean and the edge of the card is in no danger of becoming jagged.

The most modern appliance of this kind, however, will be found quoted in one of the catalogues under the name of ‘trimming-shears.’ These shears are not necessarily cheating-tools; they are largely used to trim the edges of faro-cards, which will not pass through the dealing-box if they are damaged. The shears for cleaning up cards in a genuine manner, however, are only required to cut them rectangular. In the case of those used for swindling they must cut at any desired angle.

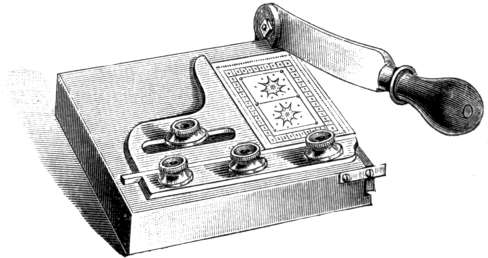

These shears consist of an oblong block of wood, into which a steel bar is sunk along one edge, carrying a bracket which supports the cutting-blade, working on a pivot at one end (fig. 46). The edge of the steel bar and the blade which works in close contact with it form respectively the lower and upper halves of the shears. Upon the upper surface of the wooden block two guide-plates are fixed, by means of thumb-screws. These plates are adjustable to any angle within certain limits, and are for the purpose of holding the cards in position whilst being cut. The guide-plates being set at the necessary angle, the card about to be cut is pressed against them with the left hand, whilst the right brings down the knife, and cuts off one edge. Fig. 46 shows a card in the act of being cut. Each card being held against the guides while cutting, uniformity of the whole is secured. When one side of each card has had a shaving taken off, if it is desired to trim the opposite side as well, the guides are adjusted to give the required width, and a second cut is taken.

Shears of this kind, of course, will not cut the sides of the cards concave; but a very good substitute for convex sides may be made by taking two cuts on each side, at a very slight angle one to the other, taking more off the corners than in the center. There is no need to impress upon the reader that the defective form of the card is not made sufficiently pronounced to be noticeable. The two cuts do not meet in the middle to form a point; the apex of the angle, so to speak, is cut off, leaving the central portion of the side flat, and square with the ends of the card.

Square-cornered playing-cards of course will show no signs of having been trimmed in this way; but those with round corners are bound to do so, however slight a shaving may have been removed from the side. In trimming these for cheating, therefore, the sharp has to employ, in addition to the shears, what is called a ’round-corner cutter.’ This is an instrument which restores the circular form of the corners, which otherwise would show the point at which the shears cut through them. It is simply a sort of punch, which cuts the corners, one at a time, into their original shape, and gives them their proper curve.

So much, then, for the tools. We have next to consider the various forms given to the cards, and the uses to which they are put when thus prepared.

The simplest device connected with cards which have been trimmed is that known as the ‘large card.’ As its name implies, it is a card which is left slightly larger than the rest of the pack. All the others are trimmed down, either slightly narrower or shorter, or smaller altogether. This is a very primitive dodge, and one seldom resorted to, in the ordinary way, nowadays. Its object is to give the sharp either a ready means of forcing the cut at a given point in the pack, or of making the pass at that point, if the cut does not happen to be made in the right place. The cards being manipulated so as to arrange them according to some particular system, the large card is placed at the bottom, and then the pack is divided at about the middle, and the top half put underneath. The pack is straightened, and laid on the table to be cut. Not suspecting any trickery, it is almost certain that the dupe, in cutting, will seize hold of the large card, which is now in the centre of the pack, and cut at that point. This brings the cards again into the positions they occupied relatively at first. If the cut, however, should not happen to be made at the ‘large,’ the sharp has to make the pass, and bring that card once more to the bottom. No modern sharp of any standing would use such a palpable fraud, even among the most innocent of his dupes. It is a long way behind the times, and was out of date years ago.

Another form of card which at one time was largely used, but which has become too well-known to be of much service, is the ‘wedge.’ Wedges are cards which have been cut narrower at one end than the other, the two long sides inclining towards each other at a slight angle. The cards when cut in this way, and packed with all the broad ends looking the same way, cannot be distinguished from those which are perfectly square; but when some are placed one way and some the other, there is no difficulty in telling ‘which is which.’ Before these cards became commonly known, they must have proved very useful to the sharp. If he wished to force the cut at any particular place, he had only to place the two halves of the pack in opposite directions, and the cut was pretty sure to be made at the right point. If he wished to distinguish the court cards from the others, all he had to do was to turn them round in the pack, so that their broad ends faced the other way. If he wished to be sure of making the pass at any card, by just turning the wide end of that card to the narrow ends of the others he could always feel where it was, without looking at it. In fact, the utility of such cards was immense, but it has long been among the things that were. Now, the first thing a tiro in sleight-of-hand will do, on being asked to examine a pack of cards, is to cut them and turn the halves end for end, to see if they are ‘wedges.’ Needless to say, they never are.

The only case in which it is at all possible to use cards of this kind at the present day is in a very, very ‘soft’ game of faro, where the players do not ask permission to examine the pack. The dealer has the sole right of shuffling and cutting the cards; therefore if he has the opportunity of using wedges, nothing is easier than to have all the high cards put one way, and the low ones the other. Then in shuffling he can put up the high cards to lose or win, and, in fact, arrange the pack in any manner he likes. There is very little safety, however, in the use of wedges at any time. Practical men would laugh at the idea of employing them.

The concave and convex cards cut by means of the stripper-plates, described earlier in this chapter, are still in use to a limited extent. The common English sharp employs them in connection with a game called ‘Banker.’ He ‘readies up the broads,’ as he terms it, by cutting all the high cards convex, and the low ones concave. There is also another game known as ‘Black and Red,’ in which the cards of one color are convex, and the other color concave.

The most commonly used form of cards, however, is that of the ‘double-wedges’ or ‘strippers,’ cut by means of the trimming-shears, and which have been already described. The name of ‘strippers’ is derived from the operation which these cards are principally intended to facilitate, and which consists of drawing off from the pack, or ‘stripping,’ certain cards which are required for use in putting up hands. Suppose the sharp is playing a game of poker, and, naturally, he wishes to put up the aces for himself, or for a confederate. He cuts the aces narrow at each end, and all the other cards of the same width as the ends of the aces. This leaves the sides of the aces bulging out slightly from the sides of the pack, and enables him to draw them all out with one sweep of his fingers during the shuffle. Then they are placed all together, at the bottom of the pack, and can be put up for deal or draft, or they may be held out until required.

‘End-strippers’ are a variety of the same kind of thing, the only difference being that they are trimmed up at the ends, instead of at the sides.

It is only in England and other countries where the spread of knowledge in this direction has been limited to the sharps themselves, the general public remaining in ignorance, that strippers are employed. They would be instantly detected among people who have learnt anything at all of sharping.

Trimming is not the only method of preparing cards for cheating purposes; there are others of much greater delicacy and refinement. Witness the following, which is culled from the circular issued by one of the ‘Sporting Houses’:—

‘To smart poker players.—I have invented a process by which a man is sure of winning if he can introduce his own cards. The cards are not trimmed or marked in any way, shape or manner. They can be handled and shuffled by all at the board, and without looking at a card you can, by making two or three shuffles or ripping them in, oblige the dealer to give three of a kind to any one playing, or the same advantage can be taken on your own deal. This is a big thing for any game. In euchre you can hold the joker every time or the cards most wanted in any game. The process is hard to detect, as the cards look perfectly natural, and it is something card-players are not looking for. Other dealers have been selling sanded cards, or cheap cards, with spermacetia rubbed on, and calling them professional playing or magnetic cards. I don’t want you to class my cards with that kind of trash. I use a liquid preparation put on with rollers on all cards made; this dries on the cards and does not show, and will last as long as the cards do. The object is to make certain cards not prepared slip off easier than others in shuffling. You can part or break the deck to an ace or king, and easily “put up three,” no matter where they lay in the deck. This advantage works fine single-handed, or when the left-hand man shuffles and offers the cards to be cut. These cards are ten times better than readers or strippers, and they get the money faster. Price, $2,00 per pack by mail; $20,00 per dozen packs. If you order a dozen I will furnish cards like you use.’

The gentle modesty and unassuming candour of the above effusion, its honest rectitude and perfect self-abnegation, render it a very pearl of literature. It is a pity that such a jewel should be left to hide itself away, and waste its glories upon the unappreciative few, whilst thousands might be gladdened by the sight of it and proceed on their way invigorated and refreshed. Let us bring it into the light and treasure it as it deserves.

As the talented author above quoted suggests, there are several methods of achieving the object set forth, and causing the cards to slip at any desired place, apart from the much vaunted ‘liquid preparation put on with rollers’ the secret of which one would think that he alone possessed. We will just glance at them all, by way of improving our minds and learning all that is to be learnt.

The earliest method of preparing a pack of cards in this way certainly had the merit of extreme simplicity, in that it consisted of nothing more than putting the pack, for some time previous to its use, in a damp place. This system had the further advantage that it was not even necessary to open the wrapper in which the cards came from the maker. When the cards had absorbed a certain amount of moisture, it was found that the low cards would slip much more easily than the court cards. The reason for this was, that the glaze used in ‘bringing up the colours’ of the inks used in printing contained a large proportion of hygroscopic or gummy matter, which softened more or less upon becoming moist. The court cards, having a much greater part of their faces covered with the glaze than the others, were more inclined to cling to the next card, in consequence. Therefore the task of distinguishing them was by no means severe.

Not satisfied with this somewhat uncertain method, however, the sharps set to work to improve upon it. The next departure was in the direction of making the smooth cards smoother, and the rough ones more tenacious. The upshot of this was that those cards which were required to slip were lightly rubbed over with soap, and those which had to cling were treated with a faint application of rosin. This principle has been the basis of all the ‘new and improved’ systems that have been put before the sharping public ever since. Either something is done to the cards to make them slip, or they are prepared with something to keep them from slipping.

When the unglazed ‘steam-boat’ cards were much in use the ‘spermacetia’ system, referred to in the paragraph quoted a little while ago, was a very pretty thing indeed, and worked well. The cards which it was necessary to distinguish from the others were prepared by rubbing their backs well with hard spermaceti wax. They were then vigorously scoured with some soft material, until they had acquired a brilliant polish. Cards treated in this manner, when returned again to the pack, would be readily separable from the others. By pressing rather heavily upon the top of the pack, and directing the pressure slightly to one side, it would be found that the pack divided at one of the prepared cards. That is to say, the cards above the prepared one would cling together and slide off, leaving the doctored one at the top of the remainder.

With glazed cards, if they are required to slip, the backs are rubbed with a piece of waxed tissue paper, thus giving them an extra polish; but the better plan is to slightly roughen the backs of all the others. They may be ‘sanded,’ as in the case of those used for the sand-tell faro-box. This simply means that the backs are rubbed with sand-paper. In reality, it is fine emery-paper that is used; any sand-paper would be too coarse, and produce scratches.

There still remains to be considered the method of causing the cards to cling, by the application of that marvellous master-stroke of inventive genius, the ‘liquid preparation,’ as advertised. It may be hoped that the reader will not feel disappointed on learning what it is. The wonderful compound is nothing more or less than very thin white hard varnish. That is all. It may be applied ‘with rollers,’ or otherwise, just as the person applying it may prefer. The fact of certain cards being treated with this varnish renders them somewhat ‘tacky,’ and inclined to stick together; not sufficiently, however, to render the effect noticeable to anyone who is not looking for it. But, by manipulating the pack as before directed in the case of the waxed cards, the slipping will occur at those cards whose backs have not been varnished. The instructions sent out with the cards mentioned in the advertisement will be found reprinted at p. 304; therefore, since it would be presumptuous to think of adding anything to advice emanating from the great authority himself, we may leave him to describe the use of his own wares.

Having thus said all that is necessary to give the reader sufficient information for his guidance in any case of sharping with which he may be brought into contact, we may bring this chapter to a close; and, in so doing, conclude all that has to be said upon the subject of cheating at cards. We have been compelled to dwell somewhat at length upon matters which are associated with cards and card-games only, because so large a proportion of the sharping which goes on in the world is card-sharping. Almost everyone plays cards, and so many play for money. Therefore, the sharp naturally selects that field which affords him the widest scope and the most frequent opportunities for the exercise of his calling. Card-sharping has been reduced to a science. It is no longer a haphazard affair, involving merely primitive manipulations, but it has developed into a profession in which there is as much to learn as in most of the everyday occupations of ordinary mortals.

With this chapter, then, we take a fond farewell of cards, for the present; and having said ‘adieu,’ we will turn our attention to other matters.