ALTHOUGH there can be no question as to the utility of marked cards in the hands of the sharper, it frequently happens that he is unable to avail himself of the advantages presented by their employment. It may be, perhaps, that he is so situated as to be compelled to use genuine cards belonging to someone else; and that the comparatively scanty and hurried marking supplied by means of poker-ring or shading box will not provide him with all the information imperatively demanded by the nature of the game in which he is engaged. He may, perhaps, be playing in circles where the devices of marking, and the methods of accomplishing it, are well known. For many reasons the use of marked cards may be too risky to be ventured upon; or the cards themselves may not be available at the. moment. Again, the sharp may not have taken the trouble to master any system of marking; yet, for all that, he requires a knowledge of his opponent’s cards just as much as his more talented brother of the pen, the brush, and the needle-point. How then, it may be asked, is he to obtain this knowledge? Simply very simply. The sharp needs to be hard pressed indeed, to be driven to the end of his tether.

Marked cards being out of the question, it is possible to obviate to a great extent the necessity for them by the use of certain little instruments of precision denominated ‘reflectors,’ or, more familiarly, ‘shiners.’ These are not intended to be used for the purpose ot casting reflections upon the assembled company. Far from it. Their reflections are exclusively such as have no weight with the majority. They, and their use alike, reflect only upon the sharp himself.

These useful little articles are constructed in many forms, and are as perfectly adapted to the requirements of the individual as are the works of Nature herself. Just as man has been evolved in the course of ages from some primitive speck of structureless protoplasm, so, in like manner, we find that these convexities of silvered glass have crystallized out from some primordial drop of innocent liquid, more or less accidentally spilled upon the surface of a table in years gone by.

Such, then, was the origin of the reflector. The sharp of long ago was content to rely upon a small circular drop of wine, or whatever he happened to be drinking, carefully spilled upon the table immediately in front of him. Holding the cards over this drop, their faces would be reflected from its surface, for the information of the sharp who was dealing them.

Times have advanced since then, however, and the sharp has advanced with the times. We live in an age of luxury. We are no longer satisfied with the rude appliances which sufficed for the simpler and less fastidious tastes of our forefathers; and in this respect at least the sharp is no exception to the general rule. He, too, has become more fastidious, and more exacting in his requirements, and his tastes are more expensive. His reflector, therefore, is no longer a makeshift; it is a well-constructed instrument, both optically and mechanically, costing him, to purchase, from two and a half to twenty-five dollars. Not shillings, bear in mind, but dollars. Think of it! Five pounds for a circular piece of looking-glass, about three-quarters of an inch in diameter! The fact that such a price is paid is sufficient to indicate the profitable character of the investment.

The first record we have of the employment of a specially constructed appliance of this kind describes a snuff-box bearing in the centre of the lid a small medallion containing a portrait. The sharp in taking a pinch of snuff pressed a secret spring, the effect of which was to substitute for the portrait a convex reflector. The snuff-box then being laid upon the table the cards were reflected from the surface of this mirror, giving the sharp a reduced image of each one as it was dealt. A device of this kind may have passed muster years ago, but it could never escape detection nowadays. At the present day card-players would be, unquestionably, ‘up to snuff.’

Among the more modern appliances, the first to which we shall refer is that known as the ‘table reflector.’ As its name implies, it is designed for the purpose of being attached to the card-table during the game. It is thus described in one of the price-lists.

‘Table-reflector, Fastens by pressing steel spurs into under side of table. A fine glass comes to the edge of table to read the cards as you deal them off. You can set the glass at any angle or turn it back out of sight in an instant.’

From the many samples similar to the above with which one meets in ‘sporting’ literature, the legitimate inference is that punctuation-marks are an expensive commodity in certain districts of America.

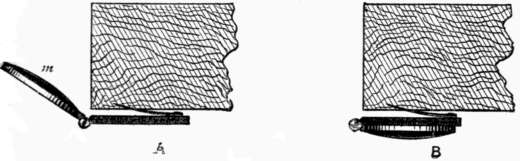

The reflector to which this paragraph refers is illustrated in fig. 20. It is a neat little contrivance, nicely finished and nickel-plated.

The mirror m is convex, forming as usual a reduced image of the card. A represents the position of the reflector whilst in use. B shows the manner in which it is turned back, out of the way and out of sight. The hinge is fitted with light friction-springs, which enable the mirror to retain any position in which it may be placed.

The correct way to ‘play’ the reflector is to press the steel point into the under side of the table, just sufficiently far back to bring the hinge about level with the lower edge of the table top. Whilst in use, the mirror, contrary to what one might suppose, is not inclined downwards, but the inclination given to it is an upward one as in the illustration. Thus, whilst the sharp is leaning slightly forward, as one naturally would, whilst dealing, the cards are reflected from the mirror as he looks back into it.

Used in this manner, the reflector can be played anywhere, and even those who are familiar with ‘shiners’ will ‘stand’ it. Inclined downwards, it may be easier to use, but in that case the dealer would have to lean back whilst distributing the cards. A proceeding such as that would be liable to attract attention and to arouse suspicions which, all things considered, had better be allowed to slumber if the sharp is to maintain that mental quietude so necessary to the carrying out of his plans. It is possible of course that nothing of the kind may occur, but, on the other hand, it might. One cannot be too careful, when even the most innocent actions are apt to be misconstrued. The world is so uncharitable, that a little thing like the discovery of a bit of looking-glass might lead to a lot of unpleasantness. Who knows?

Should anyone happen to come behind the dealer whilst the mirror is in view, it can always be turned out of sight with the little finger in the act of taking up one’s cards from the table, or by sitting very close it can be altogether concealed.

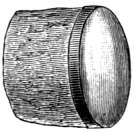

Another very efficient form of reflector is one so constructed as to be adaptable to the interior of a pipe-bowl. It consists of a small convex mirror, similar to the one used in the table reflector, which is cemented to a piece of cork shaped to fit inside the bowl of an ordinary briar root pipe (fig. 21).

Such a device is more adapted to the requirements of the second or third-rate sharper, as it would not be available in a circle of cigarette-smoking ‘Johnnies.’ It is used in the following manner.

The ‘shiner’ is carried separately from the pipe, and held until required in the palm of the hand, with the cork downwards. The sharp having finished his pipe, stoops down to knock out the ashes, upon any convenient spot. As the hand is again brought up to the level of the table, the glass is pressed into the bowl of the pipe with the thumb. The pipe is then laid upon the table, with the bowl facing towards its owner, a little to the left of where he is sitting. In this position the mirror is visible to no one but the sharp himself. He is therefore at liberty to make the freest use of it without exciting suspicion in the least.

Fig. 22.—PIPE-REFLECTOR IN SITU

Fig. 22 is a photograph of pipe and mirror in situ, which will give a far better idea of the convenience of this arrangement than any amount of explanation could possibly enable the reader to form. The card which is seen reflected in miniature was held at a distance from the mirror of about six inches.

Among the various forms in which reflectors are supplied, there are some attached to coins and rouleaux of coins of various values. Also there are some so constructed as to be attached to a pile of greenbacks’ or bank-notes. The manner in which these are used will be readily understood, therefore there is no need to do more than refer to them. In addition to these, there is the appliance described in the catalogue as ‘Reflector, attached to machine, can be brought to palm of hand at will.’ This will be found described in the chapter on ‘holdouts,’ to which class of apparatus it properly belongs.

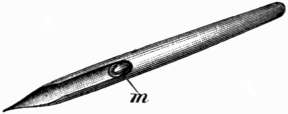

The smallest and most difficult to use of all reflectors is one the very existence of which is but little known, even among sharps, viz. the toothpick reflector. In this instance the mirror is a very tiny one adapted to lie at an angle within the interior of a large quill tooth-pick. With the exception of its size, it is similar in other respects to the pipe-reflector already described. Needless to say, the extreme minuteness of the image formed by so small a mirror entirely precludes its use except by a sharp who is an expert indeed, and one whose vision is of the keenest description: m, fig. 23, indicates the position occupied by the mirror within the interior of the quill. The noble bird typical of all gamblers from whose pinion the feather has been extracted for so unworthy a purpose, might well exclaim, ‘To what base uses may we come!’

The operator who has adopted this form of instrument will enter the room where card-players are assembled, chewing his tooth-pick after the approved Piccadilly fashion of a few years ago. Having taken his place at the table, he throws down the tooth-pick in front of him, with the pointed end turned towards him. His mirror then comes into play, in the same manner as that of the pipe-reflector aforesaid.

One form of reflector which is very useful to the sharp in a single-handed game, is that mentioned in one of the catalogues as being intended to stand behind a pile of ‘chips’ or counters upon the table. It may appear to the uninitiated that there would be great difficulty in concealing a mirror in this way. Such, undoubtedly, would be the case if only one pile of chips were used. By placing two piles side by side, however, the difficulty disappears. With counters, say, an inch and a quarter in diameter, there is ample space behind two piles, when standing close together, to accommodate and conceal a tolerably large reflector, as such things go.

The mirror in this case is mounted somewhat after the fashion of a linen-prover; and precisely resembles a small hinge. The hinge being opened, reveals the reflector. It is set at a suitable angle and simply laid upon the table, either behind the rouleaux of counters, as explained above, or behind a pile of bank-notes, .as may be most convenient. If the sharp should unhappily be compelled to part with either counters or notes a circumstance, by the way, which should never occur in the ordinary course of events though accidents will happen now and then the reflector can be closed up and secreted in an instant.

It is a neat little device, and one well worthy the notice of intending purchasers. (See advt.}

In connection with sharping of any kind, as in every other branch of art, whether sacred or profane, legal or illegal, one fact is always distinctly noticeable. No matter what improvements may be made, or what amount of complexity may be introduced into any system, or into the appliances which have been invented to meet its requirements, the practice of its leading exponents always tends towards simplicity of operation. To this rule there are very few exceptions. The greatest minds are, as a rule, content to use the simplest methods. Not the easiest, bear in mind, but the simplest. The simple tools are generally more difficult to use with effect than the more elaborate ones. The great painter with no other tools than his palette-knife and his thumb will produce work which could not be imitated by a man of inferior talents, although he had the entire stock of Rowney or Winsor and Newton at his disposal. So, in like manner, is it with the really great expert in sharping. With a small unmounted mirror, and a bit of cobbler’s wax, he will win more money than a duffer who possesses the most perfect mechanical arrangement ever adapted to a reflector. It is the quality of the man which tells, not that of his tools.

It may perhaps be asked then, if the simplest appliances are best, why is it that they are not generally adopted, in place of the more complicated devices. That, however, is just the same thing as asking why an organ-grinder is content to wind out machine-made airs during the whole of his existence, rather than to devote his time to the far less expensive process of learning to play an instrument. The answer is the same in both cases. It is simply that machinery is made to take the place of skill. The machine can be obtained by the expenditure of so much or so little money, whilst the skill can only be obtained by a lifetime of practice. Your duffer, as a rule, does not care about hard work. He prefers a situation where all the hard work is put out, and the less irksome is done by somebody else. Hence the demand for cheating-tools which will throw the responsibility of success or failure upon the manufacturer, leaving the operator at liberty to acquire just as much skill as he pleases, or to do without skill altogether if he thinks fit.

According to one of the leading experts in America, the above-mentioned bit of cobbler’s wax, in conjunction with the plain unmounted mirror, is by far the best method of employing a reflector. The mirror is simply attached, by means of the wax, to the palm of the hand near the edge; and when it is fixed in this position, the little indices, usually found upon the corners of modern playing-cards, can be read quite easily. Furthermore, so situated, the reflector is quite secure from observation.

The majority of sharps, however, appear to strike the happy medium between the simplicity of this device and the complexity of the ‘reflector attached to machine.’ Thus, it is the table-reflector which appears to be the most popular for general use, although from its nature it is not well-adapted for use in a , round game. There are too many people to the right and left of the operator. For a single-handed game, however, where the sharp has no opportunity of ‘getting his own cards in,’ it is invaluable.

Supposing, then, for the moment, gentle reader, that you were a sharp, your plan of working the table-reflector would be as follows. You would find your ‘mug’ (first catch your hare), and perhaps you might induce him to invite you to his club. Having got your hand in to this extent, doubtless you would find means of persuading him to engage you in a game of cards, ‘just to pass the time.’ He thinks, no doubt, that he is perfectly safe, as the club cards are being used, and moreover being in all probability what is known in ‘sporting’ circles as a ‘fly-flat’ that is, a fool who thinks himself wise he imagines that he knows enough about cheating to ‘spot’ anyone who had the audacity to ‘try it on’ with him. Now, if there is one thing more certain than another, it is that a sharp is always safest in the hands of a man who thinks he knows a lot. The event will nearly always prove that his knowledge is limited to an imperfect acquaintance with some of the older forms of manipulation; things which have been discarded as obsolete by all practical men. Therefore, if he anticipates cheating at all, he prepares himself to look out for something vastly different to what is about to take place. His mind running in a groove, he is preoccupied with matters which are of no importance to him; and thus falls an easy prey to the sharper.

In such a case, then, you have a ‘soft thing.’ You select a table which affords you the opportunity of securing a nice, convenient seat, with your back to the wall. You fix your ‘shiner’ just under the edge of the table, and engage your ‘pigeon’ in a single-handed game of poker. If you are worth your salt, you ought to pluck him nay, skin him, for all he is worth.