THERE are many methods of performing the manoeuvre that reverses the action of the cut, but in this part of our work we will describe but three which we consider at all practicable at the card table. This artifice is erroneously supposed to be indispensable to the professional player, but the truth is it is little used, and adopted only as a last resort. The conjurer employs the shift in nine-tenths of his card tricks, and under his environments it is comparatively very simple to perform. A half turn of the body, or a slight swing of the hands, or the use of "patter" until a favorable moment occurs, enables him to cover the action perfectly. But seated at the card table in a money game, the conditions are different. The hands may not be withdrawn from the table for an instant, and any unusual swing or turn will not be tolerated, and a still greater handicap arises from the fact that the object of a shift is well known, and especially the exact moment to expect it, immediately after the cut. The shift has yet to be invented that can be executed by a movement appearing as coincident card-table routine; or that can be executed with the hands held stationary and not show that some manoeuvre has taken place, however cleverly it may be performed. Nevertheless upon occasion it must be employed, and the resourceful professional failing to improve the method changes the moment; and by this expedient overcomes the principal obstacle in the way of accomplishing the action unobserved. This subterfuge is explained in our treatment of the subject, "The Player Without an Ally," under the distinctive heading, "Shifting the Cut."

The first shift described is executed with both hands and is a great favorite. It is probably the oldest and best in general use.

- Two-Handed Shift

HOLD the deck in the left hand, the thumb on one side, the first, second and third fingers curled around the other side with the first joints pressing against the top of the deck and the little finger inserted at the cut, or between the two packets that are to be reversed. The deck is held slantingly, with the right side downward. Bring up the right hand and cover the deck, seizing the lower packet by the ends between the thumb and second finger, about half an inch from the upper corners, the right-hand fingers being close together but none of them touching the deck but the thumb and second finger. (See Fig. 49.)

If this position is properly taken the right hand holds the lower packet and the left hand clips the upper packet between the little finger and the other three. Now, to reverse the position of the two packets, the right hand holds the lower packet firmly against the left thumb, and the left fingers draw off the upper packet, under cover of the right hand (see Fig. 50), so that it just clears the side of the lower packet, and then swing it in underneath. (See Fig. 51.)

The left thumb aids the two packets to clear each other by pressing down on the side of the under packet, so as to tilt up the opposite side as the upper packet is drawn off. The under packet being held by only one finger and thumb, can be tilted as though it worked on a swivel at each end, and the right fingers may retain their relative positions throughout. Most teachers advise assisting the action by having the fingers of the right hand pull up on the lower packet, but we believe the blind is much more perfect if there is not the least change in the attitude of the right fingers during or immediately after the shift. The packets can be reversed like a flash, and without the least noise, but it requires considerable practice to accomplish the feat perfectly. The positions must be accurately secured and the action performed slowly until accustomed to the movements.

- The Erdnase Shift-One Hand

THE following method is the outcome of persistent effort to devise a shift that may be employed with the greatest probability of success at the card table. It is vastly superior for this purpose, because the action takes place before the right hand seizes the deck, and just as it is about to do so, thereby covering naturally and actually performing the work before the action is anticipated. It is extremely rapid and noiseless, and the two packets pass through the least possible space in changing their position. The drawback is the extreme difficulty in mastering it perfectly. Many hours of incessant practice must be spent to acquire the requisite amount of skill; but it must be remembered if feats at card-handling could be attained for the asking there would be little in such performance to interest or profit any one.

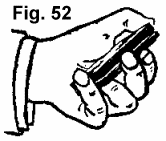

Hold the deck in the left hand, little finger at one end, first and second fingers at side, thumb diagonally across top of deck with first joint pressed down against the opposite end, and the third finger curled up against the bottom. The second fingertip holds a break at the side, locating the cut, or separating the two packets that are to be reversed. (See Fig. 52.) Now, by squeezing the under packet between the second finger and palm and pressing the upper packet with the thumb at one end against the little finger at the other end, it will be found that the two packets can be moved independently. To reverse their positions, hold the upper packet firmly by pressing with the thumb, open the two packets at the break and draw out the under packet with the second and third fingers, the second finger pulling down and third finger pressing Up, until the inner side of the under packet just clears the outside of the upper packet. (See Fig. 53.) Then press the lower packet up and over on top. When getting the under packet out and forcing it clear of the upper packet, it is turned a little by the third finger, so that the corner at the little finger end appears over the side first. The little finger aids in getting the under packet over or the upper packet underneath by pulling down on the upper packet when the lower one is just appearing over the side. (See Fig. 54.)

Doubtless the first attempts to make this shift will impress the student that it is impossible. The very unusual positions of the fingers will appear to give them no control over the deck; but the facts are the packets may be held with vice-like rigidity during the entire operation, or it may be performed by holding the packets very loosely, and in each case either in a twinkling or very slowly.

The principal difficulty will be in drawing out the under packet in such a manner that it will not fly out of the fingers. It must not spring away from the upper packet at all, but should slip along, up, and over in one continuous movement.

Of course, in performing this shift at the card table the right hand is brought over he deck just at the moment of action, and the operation may be greatly facilitated by allowing the under packet to spring very lightly against the right palm; but the finished performer will use the right hand only as a cover, and it will take no part at all in the action. We presume that the larger, or the longer the hand, the easier it will be for a beginner to accomplish this shift, but a very small hand can perform the action when the knack is once acquired.

The amateur who does not wish to spend the time necessary to perfect himself in this very difficult one-handed shift, may obtain nearly the same result by adopting the following method, which is performed with both hands and is very much easier.

- Erdnase Shift-Two Hands

HOLD the deck in the left hand as described in the one-hand shift. except that the first finger is curled up against the bottom and the third finger is held against the side. Now bring the right hand over the deck, the fingers held close together but in easy position, and insert the tip of the little finger in the break at side close to outer corner, just sufficiently to press down on corner of the under packet.

To make the shift, press down with the right little finger, and out and up with the left first finger, holding the upper packet firmly between left thumb and little finger. (See Fig. 55.) The lower packet will spring into the right palm, the top packet is lowered by the left thumb and little finger, and the bottom packet closed in on top by the left second and third fingers. This two-handed form of the shift is comparatively very easy to execute; it is extremely rapid and can be performed without the least noise.