Faro may almost be said to occupy in America the position of a national game. The methods of cheating used in connection with it are so numerous and so ingenious that it becomes really necessary to devote an entire chapter specially to them. Since there are parts of the world, however, outside America where the game is little known, and since it is necessary that the reader should understand something of it to enable him to follow the explanations, the first step must be to give some little idea of the nature of the game and the manner in which it is played. The following paragraphs, then, will contain a brief description of its salient features, and also of the apparatus or tools which are required in playing it.

We will commence with the accessories first. These are: (1) the faro-box, (2) the check-rack, (3) the cue-keeper, (4) cue-cards, (5) the shuffling-board, (6) the layout, and (7) the faro-table. These, together with a pack of playing-cards, constitute the apparatus employed. Let us take the various items in their order as given.

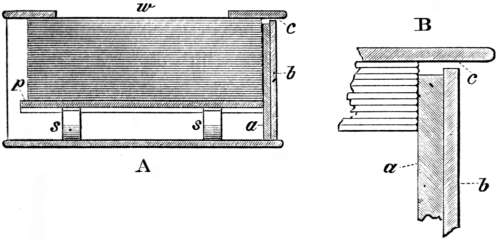

- The faro-box.—This is a metal box in which the cards are placed, face upwards, and from which they are dealt one at a time. Fig. 37 illustrates the back view of such a dealing-box.

It will be seen that the box is open at the back, and cut away at the top sufficiently to allow a large portion of the face of the top card to be visible. The plate forming the top overlaps the front side about one-eighth of an inch, and below its front edge is a slit, only just sufficiently wide to allow one card at a time to be pushed out, so that the cards are bound to be dealt one by one, and in the order they occupy in the pack. They are slipped out by the thumb, which presses upon them through the aperture in the top plate. The cards are inserted through the back, and constantly pressed upwards by a movable plate or partition, below which are springs sufficiently strong for the purpose.

It is presumable that the object of this box is to prevent any possibility of the cards being tampered with. That it not only can be made to fail in this purpose, but also to play directly into the hands of the cheat, we shall see later on.

- The check-rack.—This is a polished wooden tray, lined with billiard-cloth. It is used by the dealer, to contain his piles of counters and his money. It stands at his left hand, upon the faro-table, during play.

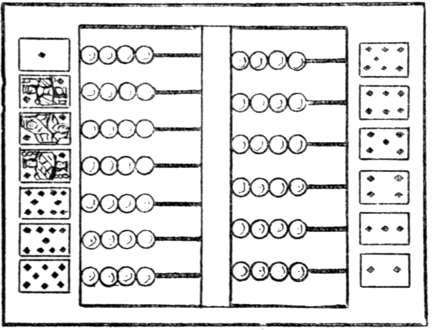

- The cue-keeper, or cue-box.—This is a piece of apparatus used for the purpose of recording the cards as they are played, and is under the control of a man who is specially told off to attend to it. By its means at any stage of the game the players can see at a glance what cards have already been played, and what remain in the pack. It is constructed upon the principle of the ancient ‘abacus’ or ‘obolus,’ and consists of a framework of wood, supporting thirteen wires, upon each of which slide four small balls (fig. 38).

Opposite each wire there is attached to the framework a miniature reproduction of one of the cards of a suit. In faro, as in poker, the suit of any card is of no importance. For all practical purposes the pack may be considered as consisting simply of four aces, four kings, four queens, and so on. Therefore, no record is kept of the suits of the cards which have been played, but only of their values. The position of the balls at the commencement of the game is at the left hand side of their respective divisions, as shown in the illustration. When a king, for example, is drawn out of the box, one ball, opposite the miniature king on the cue-keeper, is slipped to the right, and so on until all the fifty-two cards have been played, when, of course, the whole of the balls are at the right of the apparatus. The person who registers the progress of the game with this accessory is styled the ‘case-keeper.’

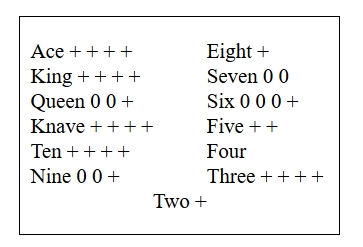

- Cue-cards.—These are small cards upon which are printed the names of the thirteen cards, a space being left opposite each name, for the purpose of enabling the players to check off the cards as they are played. They are sometimes used in place of a case-keeper; but, even where a case-keeper is employed, they are utilised by the players for recording the winning and losing cards. Any card which wins is marked with a cross, and one which loses is marked with a nought. Fig. 39 represents a cue-card which has been partially filled up in this way, and the cards which have been played so far, it will be noticed, are readily distinguishable. The cards lost are two queens, two nines, two sevens, and three sixes. Besides showing what cards have been lost and won, the cue-card also tells what cards have yet to be played. Thus, at the stage of the game indicated in fig. 39, there are still remaining in the dealing-box one queen, one nine, three eights, two sevens, two fives, four fours, and three twos. This convenient record prevents the possibility of a player betting upon cards which have already been played.

The case-keeper and cue-cards were primarily introduced with the object of keeping a check upon the dealer, and of preventing him from using a pack containing more than fifty-two cards, or in which there was not the right number of each value. We shall see presently how he manages to get over that difficulty.

- The shuffling-board.—This is a thin slab of wood or metal, covered with billiard-cloth. It stands in front of the dealer, and upon it are placed the faro-box and the piles of winning and losing cards. It is upon this board, also, that the cards are shuffled; hence its name.

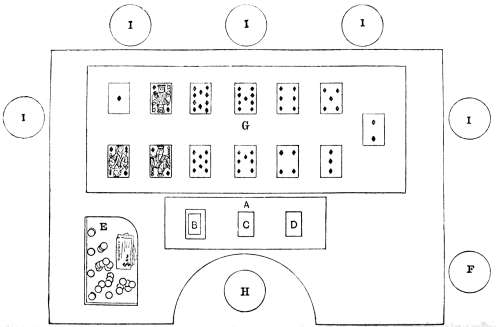

- The layout.—The designation of this adjunct to the game is derived from the fact that it forms that part of the table upon which the players ‘lay out’ their stakes. Usually it is a green cloth, having painted upon it a representation of the thirteen cards of one suit (see diagram of the faro-table, fig. 40).

- The faro-table.—This is simply an oblong table, having a recess or cavity cut out in the centre of one of the long sides. In this recess the dealer sits, being thus enabled to be as near to the layout as possible, and at the same time to have all his appliances within easy reach. Fig. 40 will give the reader a clear idea of the relative positions occupied by the dealer, the players, and the various component items of the apparatus.

a, shuffling-board. b, faro-box. c, pile of losing cards. d, pile of winning cards. e, check-tray. f, case-keeper. g, layout. h, dealer. i, i, i, i, i, players.

The appliances above described being available, the game is played in the following manner:—

At the termination of a deal the cards are all lying face upwards upon the shuffling-board in two heaps at ‘C’ and ‘D,’ and the faro-box is empty. Without taking the cards off the table, but simply turning them back upwards, the dealer mixes the two heaps together. The pack is then cut and placed with the faces of the cards upwards in the dealing-box. The players then stake their money, placing their stakes upon the layout over the card which they think will win. Each player, of course, may select any card he pleases, irrespective of the fact that another player may choose to bet upon the same card. In fact, they can all back the same card if they like. This, however, is a case which is rather rare, anyhow at the outset of a game. Meanwhile the top card of the pack has all along been visible to the players, through the aperture in the top of the box. This card, therefore, counts for nothing, and no bets can be made with respect to it. From the top card downwards, the cards alternately win for the players and the ‘bank,’ or dealer. The second card, then, when displayed will win for the players.

All the bets having been made, the dealer draws off the top card and discloses the face of the second. The top card is placed upon the shuffling-board in the position indicated by ‘C’ (fig. 40), and those players who have staked their money upon the card in the layout which corresponds in value to the card which is now seen through the window of the dealing-box will have to receive from the dealer the amount of their stakes. If no player has bet upon that card the dealer of course has to pay nothing.

The dealer has now to draw off another card from the box and display the face of the third. As explained above, this card will win for the bank. The second card is therefore drawn off, and placed upon the shuffling-board at ‘D,’ and the players who have staked their money upon the card representing the one which is now visible will lose their stakes to the dealer.

The two cards thus played constitute what is called a ‘turn.’ After each turn the dealer pays the money he has lost and receives what he has won. All money staked upon cards other than those which have either won or lost remains undisturbed upon the layout. The players are then at liberty to rearrange their bets in any manner they may think fit, and the game continues. Again the top card is removed from the box, revealing a fourth, and placed upon the card already at ‘C.’ As before, those who have staked upon the card now showing in the box receive the amount of their bets in due course. And so on until no more cards remain in the box.

There is one advantage enjoyed by the dealer in which the other players do not participate. When it so happens that both cards of a ‘turn’ are of the same value, both kings, for instance, such an occurrence is termed a ‘split,’ and a split means that the bank loses nothing, but, on the contrary, takes half the money, if any, which is lying upon the card of that value in the layout. This advantage or refait gives the bank a preponderance of the chances to the amount of about three per cent.

The above is the simplest form of the game; but, in reality, it is usually played in a more complicated manner. For instance, the players can ‘string their bets’; that is to say, they can bet on more than one card at a time. A counter placed between any two cards signifies backing either of the two cards to win, and then the player will win if either of those cards wins, or lose if either loses, and so on. A single counter may be so placed as to back all the high cards to win, and the low ones to lose, or vice versa. By ‘coppering,’ or, in other words, placing a special counter called a ‘copper,’ upon his stake, a player can bet that any card will lose instead of win.

With this short explanation of the game, we will proceed to consider the various methods of cheating at faro.

The swindling which is practised in connection with this game, and for which it affords ample scope, may be divided into two kinds. Firstly, where the players cheat the bank; and secondly, where the bank cheats the players. This latter class may again be considered under two heads, viz. cheating with fair cards and fair boxes, and cheating by means of prepared cards and mechanical arrangements connected with the faro-box and other appliances of the game.

We will take, first of all, the methods employed by the players to cheat the bank. This is done where the players are professional sharps who have contrived to ‘put up a mug’ (i.e. to persuade a dupe) to take the bank. The general practice is for one of the conspirators to have a room of his own laid out for the game, and into this very private room the victim is decoyed. In a case of this kind the ‘rig is worked,’ or in other words the swindle is perpetrated, by means of a dealing-box, so constructed as to enable the players to know what cards will win for them, and what will win for the bank. With this knowledge they run no risk of staking their money on the wrong cards. The contrivances for effecting this desirable result are known as ‘tell-boxes.’ Broadly speaking, these are of two kinds, the ‘sand-tell’ and the ‘needle-tell.’

The sand-tell box is so called because it is used in conjunction with prepared cards, which have been ‘sanded’ or roughened on one side, or both sides, as the case may be.9 The cards which are intended to ‘tell’ are left smooth on their faces; all the others are slightly roughened on both sides. The effect of this mode of preparation is that, whilst the cards which are roughened on both sides will tend to cling together, any card which lies immediately upon the smooth face of a ‘tell-card’ will slip easily.

The box with which these cards are used is shown in fig. 41, which represents a section taken through the center of the box, from top to bottom. Referring to ‘A’ in the illustration, s, s are two of the springs which press upwards upon the partition p, this in turn keeping the cards tightly pressed against the top of the box, in which the aperture or window w is cut. These details are of course common to all dealing-boxes, as already explained. The trickery, however, in this instance is in connection with the front side of the box. Instead of being of an equal thickness all round, the front is made double. That is to say, an additional plate of metal is put inside the box, covering the whole of the front plate, except that it does not reach the top by the thickness of two cards.

‘B’ in the illustration represents an enlarged sectional view of the mouth of the box. The additional plate is shown at a; b is the normal thickness of the front, and c is the slit through which the cards are pushed out.

The prepared cards being put into a box of this description, the effect produced in dealing is as follows. If the third card from the top is one of those which has been roughened on both sides, the second card will adhere to it; consequently the act of drawing off the top card will not cause the second to alter its position in the box. If, however, the third card should happen to be one of the tell-cards, whose face has been left smooth, the top card will draw the second one a little distance to the right over the top of the plate a. The second card, however, cannot be drawn right out, because the slit c is not wide enough to allow more than one card to pass at a time. It is obvious, then, that if the players have some means of knowing whether the second card moves or not, they can tell whether the card immediately underneath it is a tell-card or the reverse.

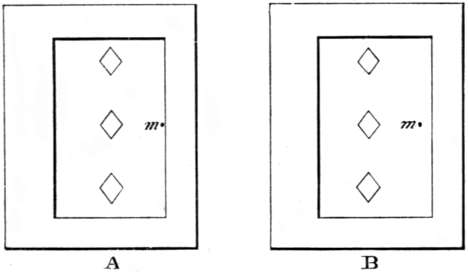

On reference to the illustration it will be manifest that the actual distance moved by the second card when drawn aside in this way can only be very slight. Indeed, it would not do to allow of much movement, or the dealer might notice it. Therefore, special means have to be adopted to enable the sharps to detect the small difference in the position of the cards. The necessary indication is readily obtained by means of what are known as ‘sighters.’ These are simply minute dots upon the faces of the cards. Upon each card one of these dots is placed, in such a position that when the card comes to the top the dot will be close to the edge of the aperture, but if the one below it is a smooth or tell-card, the slipping sideways of the card brings the dot away from the edge, and it appears farther to the centre of the opening. Fig. 42 is a diagram representing the top of a sand-tell box under both conditions. The dot marked m is the sight. In practice, it is much finer than here shown, being in fact only just visible. ‘A’ indicates the position of the dot when the card below happens to be one which has been roughened. ‘B’ shows the card drawn to one side, bringing the dot away from the edge, thus intimating the fact that the card immediately underneath is a tell-card, the face of which has been left smooth.

The general practice is to make all the court cards ‘tell.’ The advantage thus gained is that it is not necessary to bet on any particular card, but simply to back the high cards to win and the low ones to lose, or vice versa. This is not so liable to cause suspicion as having all the aces, for instance, to tell. In a case of this latter kind, the slipping of the card would indicate that the next card to be revealed would be an ace; therefore, if the conspirators are to win, at least one of them must bet upon an ace turning up. Whereas, if all the picture cards are made to tell, not only are there more tell-cards in the pack, but it is only necessary for one player to bet upon the high cards generally. The box simply tells them that a high card will show next, and they make their bets accordingly.

Of course, it would never do for all the players to stake their money alike. That would let the cat out of the bag, with a vengeance. No; if the next card is to be a high card, one of them will bet upon the high cards; the others will bet upon particular small cards, avoiding the high ones. They cannot possibly lose on the next card, because they know that it is not one of the low cards which comes next.

It will be remembered that, in the description given of the game, we saw that the bets are made just before the dealing out of each pair of cards or ‘turn.’ Therefore the indication given by the tell-box is only of use to the players before a turn commences, that is to say, before the first card of the pair is shown. They cannot change their bets until the second card of the pair is shown and the turn is played. Therefore, supposing the box indicates that the first card of the next turn, the one that wins for the players, is a court card, and that one of the players has consequently backed the high cards, the others must be careful how they arrange their bets. It may happen that one of them has put his money upon a card which will be the next to turn up; and this being the one which wins for the bank, that stake will be lost. Therefore, they have to arrange matters so that the highest stake which can possibly be won by the dealer is less than that of the player who has staked his money upon the card or cards which they know will win on the first draw. Or it may be that the other players will ‘copper’ their bets upon the low cards and thus play for absolute safety.

These manœuvres are necessary, and are here pointed out because they may be of assistance as a guide to the investigation of suspected cases of cheating by the means just described. If it should be found that, in a game of faro, it constantly happens that one of the players—not necessarily the same player—always wins on the first card of a turn, and that on the second card the others either do not lose at all, or, at any rate, that the amount which either of them loses is less than that which the other has won, it may be safely inferred that cheating is in progress.

The second kind of tell-box, which is used for the same purpose as that we have just investigated, we have already referred to as the ‘needle-tell.’ This box is also used with prepared cards, but the preparation is of a very different kind. In this instance there is no roughening of the surfaces of the cards, but those which are required to tell are cut to a slightly different shape to the others. In some respects the needle is an improvement upon the sand-tell; the cards are more easily shuffled than is the case with the ‘sanded’ ones, the clinging of which might arouse suspicion with an intelligent dealer. The dealing-box, however, is more complicated in its construction.

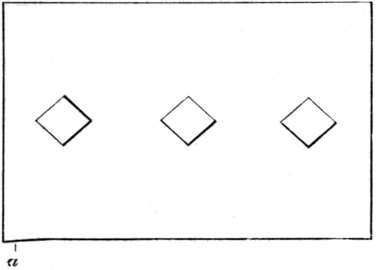

The tell-cards are cut with a slight projection at one end. Fig. 43 will give an idea of the exact shape. The projecting end will be noticed at a. Needless to say, in the cards actually used the defect in the card would not be more pronounced than is absolutely necessary.

The dealing-box is so constructed that when either of the tell-cards arrives at a certain position (usually the fourth or eighth card from the top) the projecting corner presses against a light spring and causes a little ‘needle’ or point to project from the side of the box. Frequently one of the rivets with which the box is put together is made to push out a little. Whatever the index may be, however, it does not move sufficiently to attract attention. It is only those who are looking for it who know when it ‘tells.’ A movement of one thirty-second of an inch is ample for the sharp eyes of the swindlers to detect.

The mechanism of the needle-tell, however, is not used solely in connection with cases where the players cheat the bank, it also forms a very necessary accessory to the ‘two-card’ box to be presently explained. Then it is used to let the dealer know when he is coming to the ‘odd,’ or fifty-third card.

Having thus elucidated the comparatively simple methods used to cheat the dealer, we now proceed to investigate the more complex devices employed in those cases where the bank cheats the players. As stated in the earlier part of this chapter, the players may be swindled either with fair cards and a fair dealing-box, or by means of mechanical appliances.

When the dealer elects to cheat without the use of mechanism, he is, of course, compelled to resort to manipulation, and to ‘put up’ the cards in such a way that they will help him to win. The reader will doubtless remember that in the description of the game ‘splits’ were mentioned as winning for the dealer. That is, when both cards of a turn are of the same value, the dealer takes half the money staked on the card which has split, or turned up twice in succession, the suits, of course, not counting. It is obvious, then, that if the dealer in shuffling the pack can contrive to put up a number of cards in pairs of the same value, his chances of winning are greatly enhanced. Splits, therefore, are the stronghold of the faro dealer’s manipulation. If he can only make them plentiful enough without leading the players to suspect anything wrong, he is bound to win in the long run, and to win plenty.

Whilst dealing out the cards in the first game, the dealer determines in his own mind what cards he will make split in the second game. We will suppose he has just drawn a nine from the box, and that this card has to go into pile ‘C’ (fig. 40). Now, by the laws of the game he is bound to place this card upon the top of the pile to which it belongs, therefore he does so. He may, however, with apparent carelessness, place it just a little on one side, so that he can distinguish it from the other cards. He now waits for the appearance of another nine, and this time one which will have to go into the other pile, ‘D.’ This one is disposed in the same manner. He has in sight, therefore, two cards of the same value, and if these two cards can be brought together during the shuffle, they will constitute a split. Seizing a favorable opportunity in evening up the two piles of cards, he may skillfully ‘strip’ the two nines—that is, draw them out from the others and place them at the bottom of their respective piles. There is no fear of losing them now; they are always to hand when required.

It is not necessary, however, that the cards should be put at the bottom. So long as they are each in the same position, in the pile to which they respectively belong, that is all the dealer needs. Suppose the ninth card from the bottom of pile ‘C’ to be a king, all the man wants is to have the ninth card of pile ‘D’ a king also. If, therefore, the ninth card of that heap is placed a little to one side, and all the succeeding cards are put above it in like manner, that will leave a division in the pile, into which a king can be stripped at a convenient moment.

If the players are sufficiently lax to allow the dealer to throw the cards carelessly into two heaps, instead of making two even piles, the case is, of course, much simplified. He has only to put the cards directly at the bottom or wherever else he may desire to have them.

Given the fact of certain cards having been placed in pairs, one of each pair in the same position within its pile, the problem which presents itself for solution is, How can the dealer shuffle the two piles one into the other, so as to bring the proper cards together? In short, How are the splits put up?

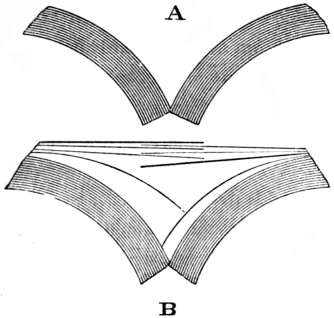

This is accomplished by means of what is called the ‘faro dealer’s shuffle.’ It must not be thought that this manipulative device is essentially a trick for cheating; on the contrary, it is an exceedingly fair and honest shuffle, provided that there has been no previous arrangement of the cards. By its use, a pack which has been divided into two equal portions may have all the cards of one half placed alternately with those of the other half at one operation. In faro, the manner of dealing the cards necessarily divides them into two equal parts. This being the case, they are taken up by the dealer, one in each hand. Holding them by the ends, he presses the two halves together so as to bend them somewhat after the manner shown in fig. 44, in the position ‘A.’ The halves are now ‘wriggled’ from side to side in opposite directions, with what would be called in mechanism a ‘laterally reciprocating motion.’ This causes the cards to fly up one by one, from either side alternately, as indicated in the figure at ‘B.’ Thus it is evident that those cards which have been placed, with malice aforethought, in corresponding positions in the two piles, will come together in a shuffle of this kind, and form splits. This shuffle is a very difficult one to learn; but with practice and patience it can be accomplished, and the cards can be made to fly up alternately, without any chance of failure. A dealer, skilled in the devices we have just touched upon, can put up four or five splits in one deal, if he thinks it advisable so to do. By the use of such means he is also enabled to arrange the cards so as to checkmate any player who may appear to be following some particular system of betting. Finding that the players are, on the whole, inclined to back the high cards, the dealer may so arrange the pack that the low cards only win for them, the high ones falling to the bank. In this, however, he runs a great risk. It may happen that the players, finding themselves constantly losing on the high cards, may alter their mode of play, and back the low ones. That would be bad for the bank unless the dealer had a mechanical box which enabled him to alter the run of the cards. Such boxes, however, are obtainable; and their description is included in the branch of our subject which treats of cheating the players by means of mechanical contrivances, and to which we now proceed.

In cases where the dealer uses apparatus for cheating, his requirements are three in number. Firstly, he must have what is known as a ‘two-card’ dealing-box, that is, a box which will allow him, whenever he pleases, to withdraw two cards at one time, instead of compelling him to deal them singly. Secondly, he must have an ‘odd,’ or fifty-third card. Lastly, he requires a mechanical shuffling-board, which adds the ‘odd’ to the pack, after the cards have been counted at the commencement of the game.

The two-card box is one of the most expensive cheating tools a sharp can use. The prices charged for them are something exorbitant, as may be seen on reference to the catalogues. To be of any use, however, they must be well-made, and then they will earn their cost in a very little time. Badly-made, the sharp would find that, however cheap they appeared to be, they would really be the most expensive and ruinous contrivances he had ever known. They are made in many varieties, and known by as many poetic names, but the effect is the same in all cases. Pressure being applied to some part of the box, the mouth is caused to open sufficiently wide to allow two cards to be drawn out together. The best boxes are those high-priced commodities of which the catalogues say that they will ‘lock up to a square box.’ This does not mean a rectangular box, but a box that will bear examination. ‘Fair’ and ‘square,’ in this instance, mean the same thing. The only fault in the description is that the box, being false, cannot possibly become genuine with any amount of locking. It should be said that when locked it appears to be genuine, and may be examined without fear of the trick being detected. Some boxes are made to lock by sliding them along the table. The bottom moves a little, this movement serving to fix all the movable parts. Some are so arranged that they are always locked. That is their normal condition, so they can be examined at any time. When it is required to widen the mouth and allow two cards to pass out together, a small piece of wire, or ‘needle’ as it is called, is made to rise out of the shuffling-board or table; this, pressing against one of the rivets, or into a little hole in the bottom of the box, unlocks the mechanism for the moment. Another form of the two-card box is one which has the bottom plate made of very thin metal, the ‘springing in’ of which, when pressed upon in the centre, unlocks the ‘fake.’ Some of the forms which unlock by sliding on the table are the most complicated, requiring sometimes three movements to free the working parts and allow the slit to widen. The movements, of course, have to follow in proper succession, as in any other kind of combination-lock. This prevents any accidental unlocking of the box whilst it is in the hands of strangers.

At the beginning of the game, then, the cards are counted to make sure that there are the proper number, and we will suppose that the dealing-box is a two-card with needle-tell attachment. One of the cards in the pack, therefore, will be cut with the projecting corner. We will suppose it to be the king of diamonds. Another king of diamonds, also cut to ‘tell,’ is held out in the mechanical shuffling-board. Whilst shuffling the cards, the dealer causes the holdout to add the ‘odd’ card to the pack. Thus there are two kings of diamonds in use.

The cards being put into the dealing-box the game begins. The dealer keeps his eye upon the needle-tell, and meanwhile unlocks the mechanism of his box; that is, if it is made to lock, which is not necessarily the case, although safer. When the needle indicates the fact that one of the duplicate cards—in this case a king of diamonds—is immediately below the top card in the box, the dealer has to be guided by circumstances. If the card will win for him, well and good. He deals the cards as they should be dealt and the king falls to him. It is evident that it would never do to have two kings of diamonds turn up in the game, the cue-keeper and cue-cards would record five kings. So the dealer still watches the needle, and when he finds that the second king of diamonds is the top card but one, he exerts the necessary pressure upon the box to widen the slit. Then, instead of withdrawing only one card two are passed out together, and placed as one upon one of the piles. This squares accounts with the case-keeper.

It may happen, of course, that when the first of the tell-cards comes to the top it would lose for the dealer. In that case he would work the ‘squeeze,’ and deal out the odd card with the one above it. Then he has to take his chance with the second of the duplicates, and the game becomes simply what it would be if honestly played. The advantage to the dealer resulting from the employment of the ‘odd’ is that it provides him with the means of winning, or at the worst prevents him from losing on one turn of the deal. This may not seem very much, but added to the chances of splits turning up it really means a great deal.

When the dealer is a proficient in sleight-of-hand he will carefully note the line of play adopted by certain ‘fat’ players, or, as the unenlightened would say, players who bet heavily. During the next shuffle he will put up the cards so as to cause these ‘fat’ men to lose, and somewhere about the middle of the pack he will place the ‘odd.’ Or it may be he will so arrange matters that the shuffle and the cut will bring one of the duplicate cards about a third of the way down the pack and the other a third of the distance from the other end. Thus he will have two opportunities of withdrawing two cards at once, either of which he can use as may suit him best.

Supposing that hitherto the heaviest betting has been on the high cards, the dealer will put up the pack in such a way that only the low ones win for the players. That is to say, the cards will come out alternately high and low, the high ones falling to the bank. As the game proceeds the first of the tell-cards by degrees comes nearer and nearer the top, and the dealer looks out for the needle-tell to indicate its approach. By this time, perhaps, the players may have noticed that the high cards are losing, and therefore may have altered their play, betting now upon the low cards. If this is so, the bank will begin to lose, but not for long. When the tell-card has become the second from the top the dealer manipulates the two-card device and draws out two cards at once. The run of the game is now altered. The cards still come out alternately high and low, but the high cards now go to the players. As they have taken to betting on the low ones they lose in consequence. If, however, the players show no signs of changing their mode of betting when the first tell-card nears the top, the dealer does not alter the run of the cards, but goes straight on. When he comes to the second duplicate card he must deal out two at once, or the ‘odd’ would be discovered.

The cases given above are put in the simplest form, for clearness; but it must not be imagined that anyone investigating a suspected case of cheating would find the cards arranged to come out always high and low alternately. The dealer knows better than to risk anything of that kind. He would be caught directly. The cards are merely put up in a general sort of way, so as to give a preponderance in one direction or the other; the dealer being at liberty to alter the general run of the cards at either of the two duplicates. Of course he might even have two extra cards in the pack, these and their duplicates being tell-cards. That would give him a choice of two out of four opportunities of altering the run; but the more devices he employs the greater the chances of detection. One turn in the deal is plenty. It gives the dealer all the opportunities he needs; and in the long run he is bound to win. It is said that in some ‘skin’ houses in New York decks of 54, 55, or even 56 cards are frequently played on soft gamblers.

It is possible for the dealer and players alike to be in a general conspiracy to cheat the bank. The dealer is not necessarily the banker. The bank may be found by anyone; the proprietor of the gambling saloon, for instance. But a dealer would be very foolish to cheat his employer. In a private game, if a dupe can be put up to find the bank in money, that is all right for the sharps. They are, one and all, at liberty to go in and win—and they do.

The reader may be interested in knowing that in America some of the dealers who are employed by proprietors of gambling houses, or saloons as they are called, will demand a salary of four or five thousand dollars. It is said that a very expert dealer is worth that amount per annum, and that he can get it. It strikes one as being a somewhat high rate of pay for a man whose sole duty is to shuffle and deal out cards for a few hours a day, if that is his sole duty. Suspicious persons—and there are a few such in the world—might be tempted to believe that there is more in the dealer’s duties than meets the eye, and a ‘darned sight’ more. Whatever opinion may be entertained upon the subject, we can all join, at any rate, in hoping for the best, and in praying for the bettor. Though when a man is idiot enough to lose his money, as some do day after day, in a game where his own common sense ought to tell him that he stands every chance of being cheated, he may be looked upon as a hopeless case. There is nothing that will ever knock intelligence into him, or his gambling propensities out of him. The only system of treatment that could be expected to do him any good would be a lengthened course of strait-waistcoat, to be repeated with additions upon any sign of a recurrence of the malady.

Two or three years ago an Englishman won 5,000 lbs in one year at the Cape, in a sort of rough-and-tumble game of faro. He ran the bank without either cue-cards or case-keeper, and also without a dealing-box, as in the prehistoric times in America before the losses experienced by those who ‘bucked against the tiger’ forced these implements into use. He dealt the cards out of his hand. The miners played against him for gold-dust and he nearly always won. His operations were of the most primitive kind. He simply had a lot of packs of cards, apparently new, but which had been opened and arranged. Some were packed for the high cards to win; some for the low ones. He would take a pack down, give it a false shuffle and begin to deal it. If he wanted to alter the run of the cards, he could at any time do so by merely dropping the top card on the floor. This he did very cleverly, and nobody noticed it, because the floor was always littered with used cards. Having no case-keeper to record the game, the missing cards were never missed. What about the poor miners? Well, they must have been flats if their equilibrium remained undisturbed through a lively game such as that. They deserved to lose all that the dealer won.

This sharp is now in England ‘mug-hunting.’ He is at present acting as bear-leader to a young man who has just come into 1,700 lbs. a year. He makes most of his living at ‘lumbering’ and ‘telling the tale,’ and his stronghold is the bottom deal. The writer has great pleasure in acknowledging his indebtedness to him for much of the information as to the methods of the common English sharp. He is a swindler, but a most agreeable and gentlemanly one.

This Faro is a hard-hearted monarch whose constant delight appears to be a slaughter of the innocents; though one can hardly suppose that his victims are often the heirs male of Israel. Be that as it may, however, Faro’s victims can hardly hope for succour from a daughter of Faro, for his only offspring are greed and fraud. And those who bow the head and bend the knee to Faro are simply ministering to these two, his children. Those who waste their substance on Faro are merely forging fetters for their own limbs, and giving themselves body and soul to a taskmaster from whose thraldom they will find it difficult to escape.

To descend from metaphor to matter of fact, there is no game which gives freer rein to the passion of gambling than faro. There is no game in which money is lost and won more readily. Above all, there is no game in which the opportunities of cheating are more numerous or more varied. If these are qualities which can recommend it to a man of common sense, call me a gambler.